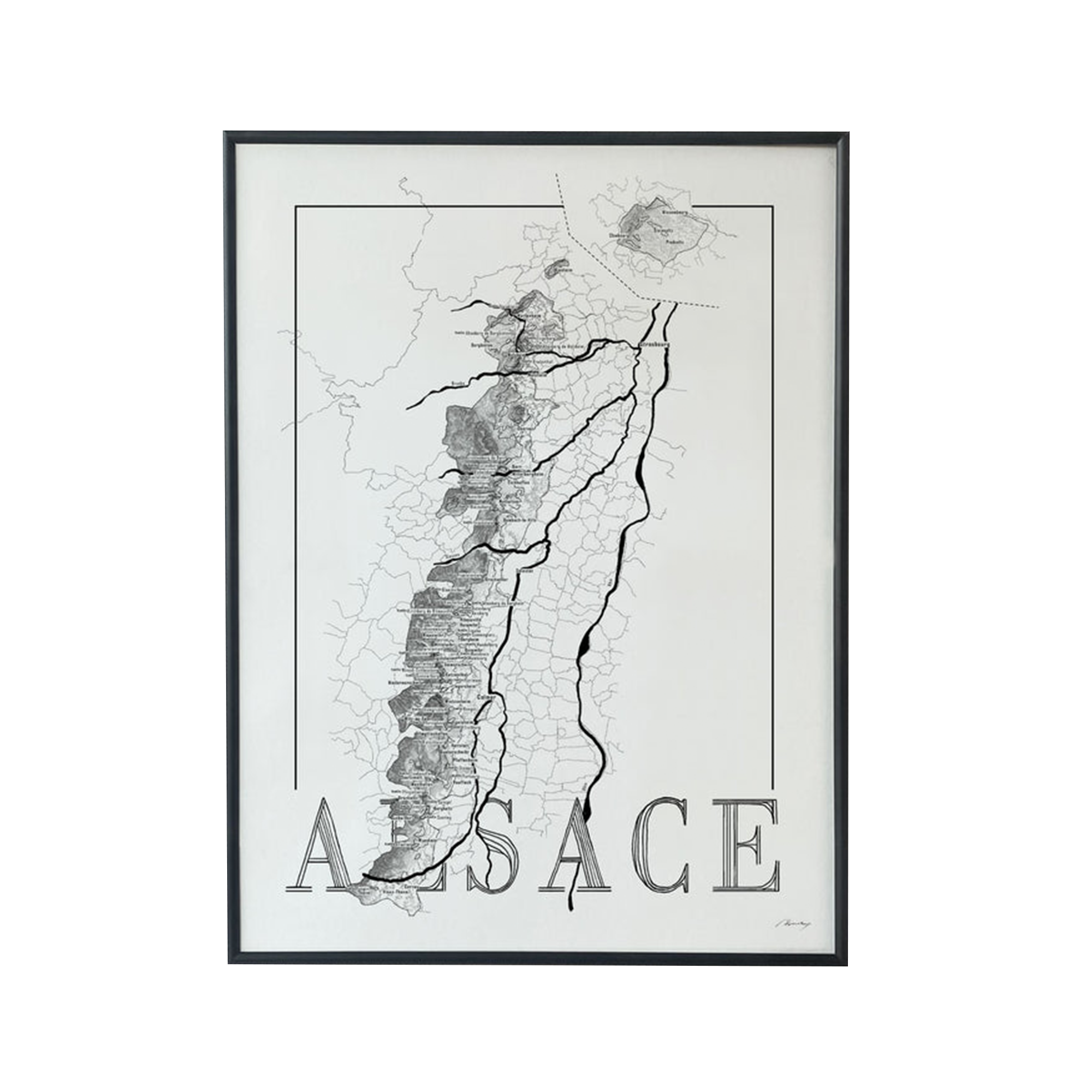

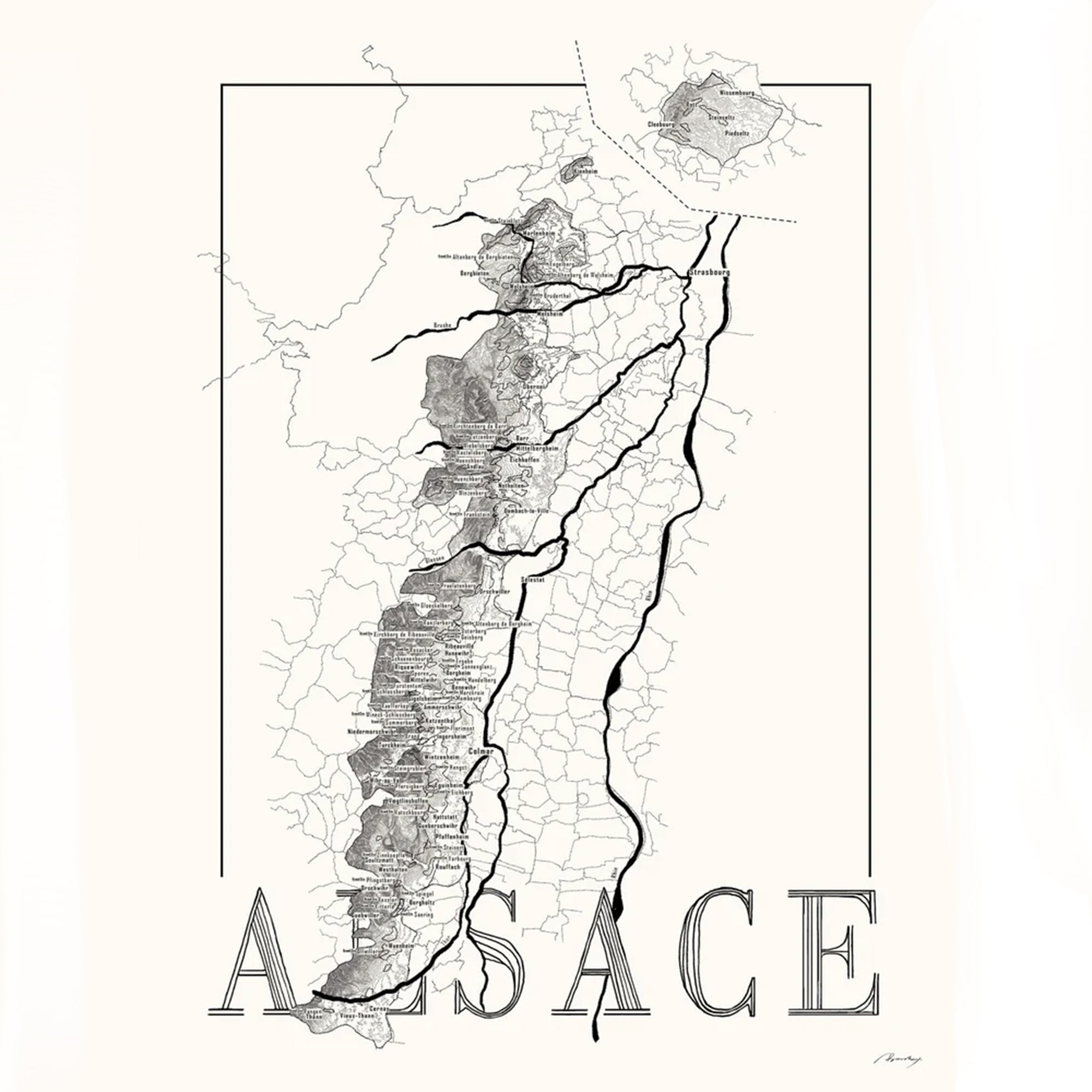

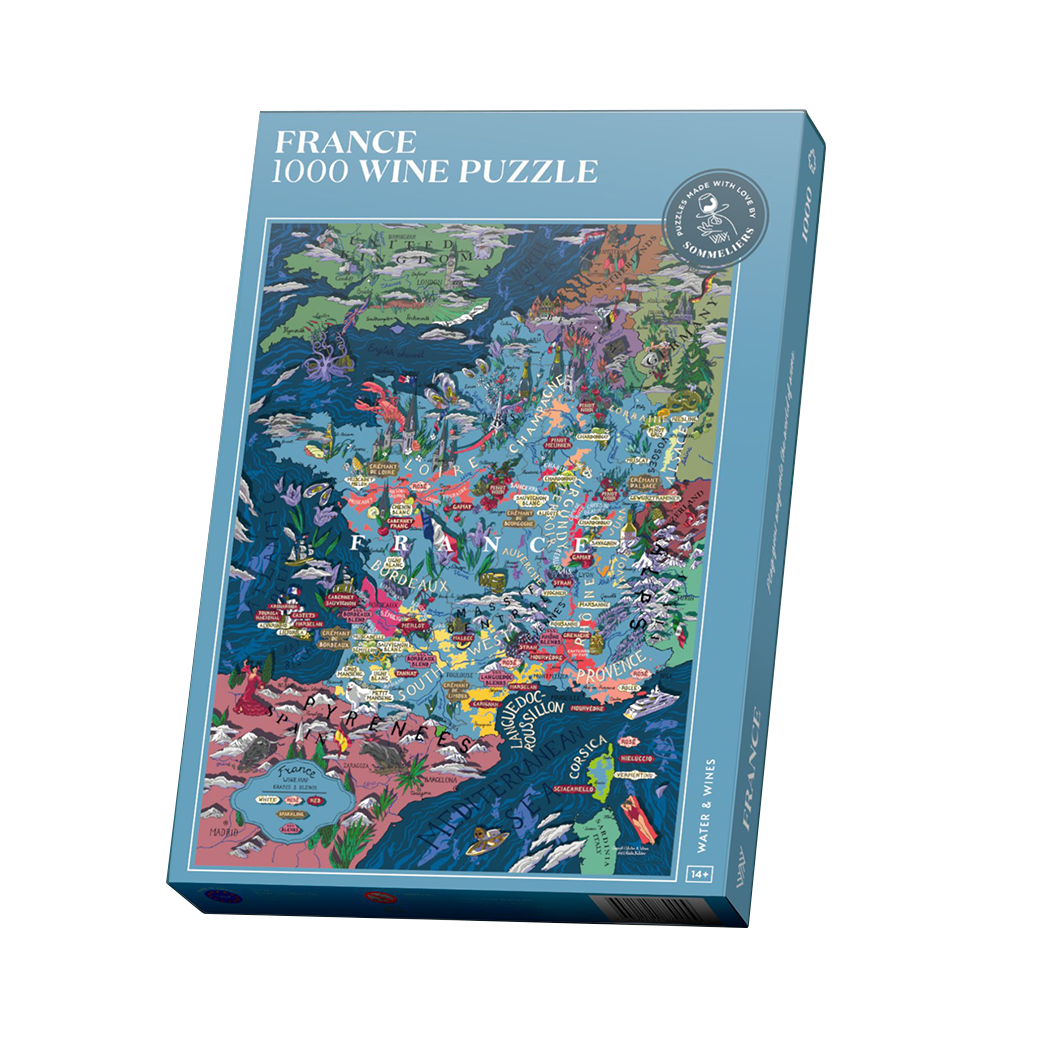

At the beginning of summer, I attended the Alsace Rocks tasting at Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam. The idea behind the tasting was to introduce you to the effect of different soil types on the wine's flavor. While interesting in itself, I often found the wines served unexciting, or interesting but overpriced. One wine stood out: the oak-aged Sylvaner from Domaine Moritz. Since I was in Alsace with my tasting group from the vinology program, a visit to that domaine was a must.

Jelmer and Putin

Domaine Moritz has existed since 1979 and has been in the hands of a Dutchman since last year. Jelmer Witkamp is the son-in-law of founders Claude and Agnès Moritz and is now the only Dutch winemaker in Alsace. We ran into Claude regularly, so the rest of the family certainly still has a hand in the business. We also encountered the neighbor's black cat. He often pottered around in the cellar, at least keeping the mice at bay. However, because he mostly came in uninvited, Jelmer called him Putin. An appropriate name these days.

Organic

A major advantage of having a Dutch winemaker is, of course, that we could just speak Dutch. For me, that's much better than speaking French. Domaine Moritz has always tried to use minimal pesticides and work as naturally as possible, but since Jelmer took over, they've also been working towards organic certification. To actually obtain that certificate, you have to work organically for three years. They're currently working on that, and by 2024 they should be officially organic. The estate produces around 40,000-50,000 bottles per year from 9.5 hectares of vineyards. They sell the rest of the grapes.

Foeders and barriques

In Alsace, a great many wines are aged in foeders. These are sometimes tall barrels that are often decades old. The purpose of these foeders is not so much to impart the flavors of the oak to the wines. That is no longer possible with foeders that have been in use for so long (unlike New barriques ). The main thing is that the wine receives just a tiny bit of oxygen, allowing it to age differently than it would if only stainless steel tanks were used. Too much oxygen, however, is not good. The wine would literally oxidize. Therefore, casks of all sizes are used, ensuring a cask is always full and that there is as little air as possible within the cask itself. Depending on the harvest size of a particular plot or grape variety, the appropriate cask size is chosen to age that specific wine. However, if a cask is not used for a year, it dries out, creating the risk of leaks. This is what happened at Domaine Moritz this year. The leak must then be sealed, of course, but the wood also needs to become more moist. To achieve this, they have now filled the cask with water. With a 10,720-liter foeder, you're essentially filling a swimming pool... Jelmer is considering selling that largest and oldest foeder (150 years old) because he doesn't expect to ever completely fill it with wine. Our big question: how do you get that foeder out of the cellar? Take it from me, it won't fit through the door by a long shot. However, the foeder can be completely disassembled by removing the steel rings. You can then simply detach the wooden planks and reassemble them elsewhere. The wood is shaped in such a way that this should work perfectly, and someone else can simply reuse the foeder. Fascinating.

The wines

It's always fun to delve into a specific topic like 'foeders'. But: how about the wine? We were treated to a very extensive tasting, which naturally included the wine that made such an impression on me: the oak-aged Sylvaner. The name of this wine is simply 101. Well, 'simply'... it has quite a meaning. 101 is a numerical representation of what's known in America as 'the basics of how you do something.' And that basics are evident in everything about this wine. It's the very first wine Jelmer made after his winemaking training, using grapes that Claude more or less had left over. He truly wanted to make a wine that only covers the basics. The grapes are pressed, and then the wine is aged in barriques without any further intervention. Unlike the foeders, these barriques do impart a slight woody aroma. Jelmer also goes back to basics for the bottle and label: it's a completely transparent bottle. The label is simply plain white printer paper with only the bare essentials in typewriter font. That doesn't mean you can call this a basic wine, though.

It's simply become a brilliant wine, and you can taste it. It's now on tap at Walsjérôt.

If you have the opportunity to sample more from Domaine Moritz, go for the Sylvaner 23: a superb wine with beautiful fruity aromas of apricot and orange peel, as well as hints of almond paste. Delicious.

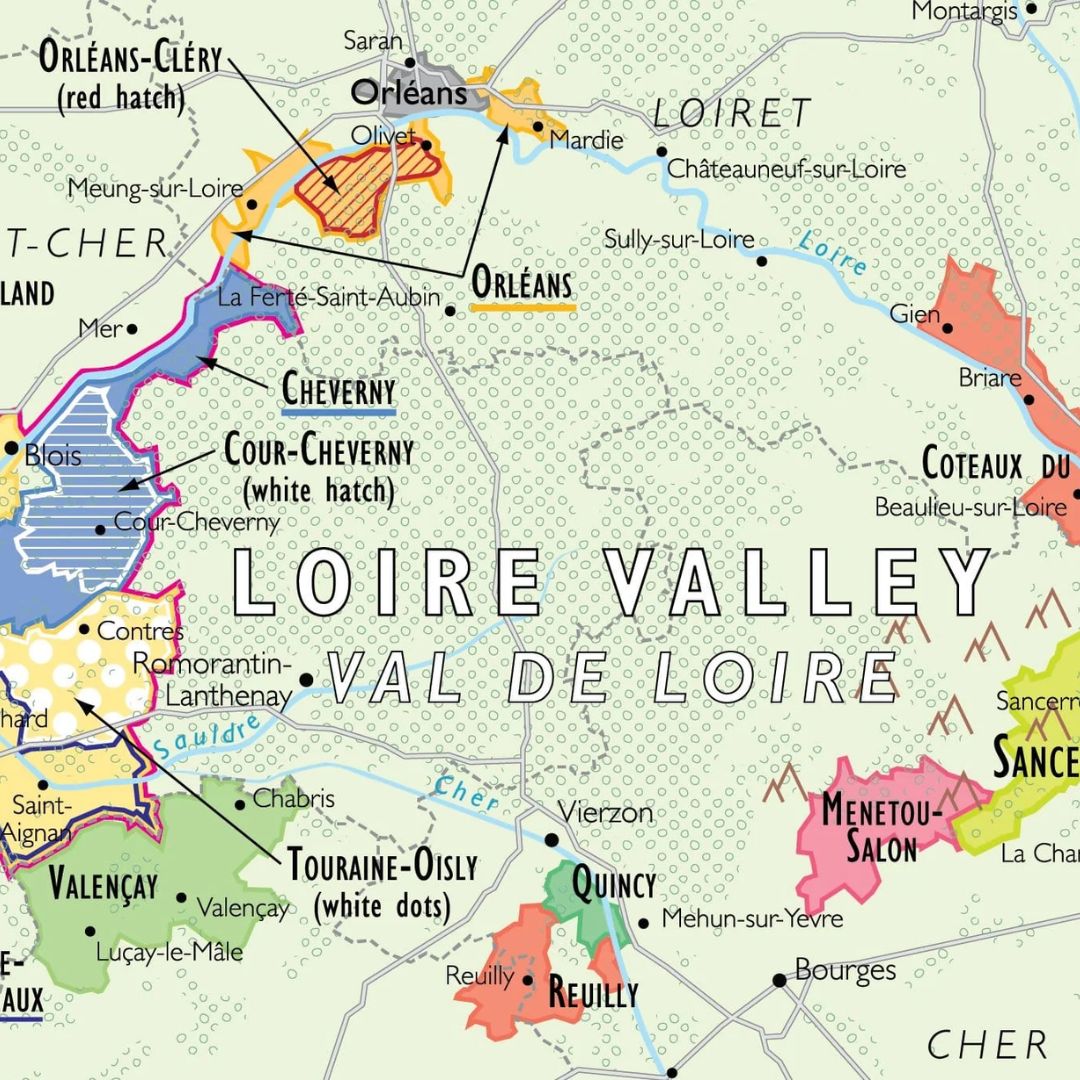

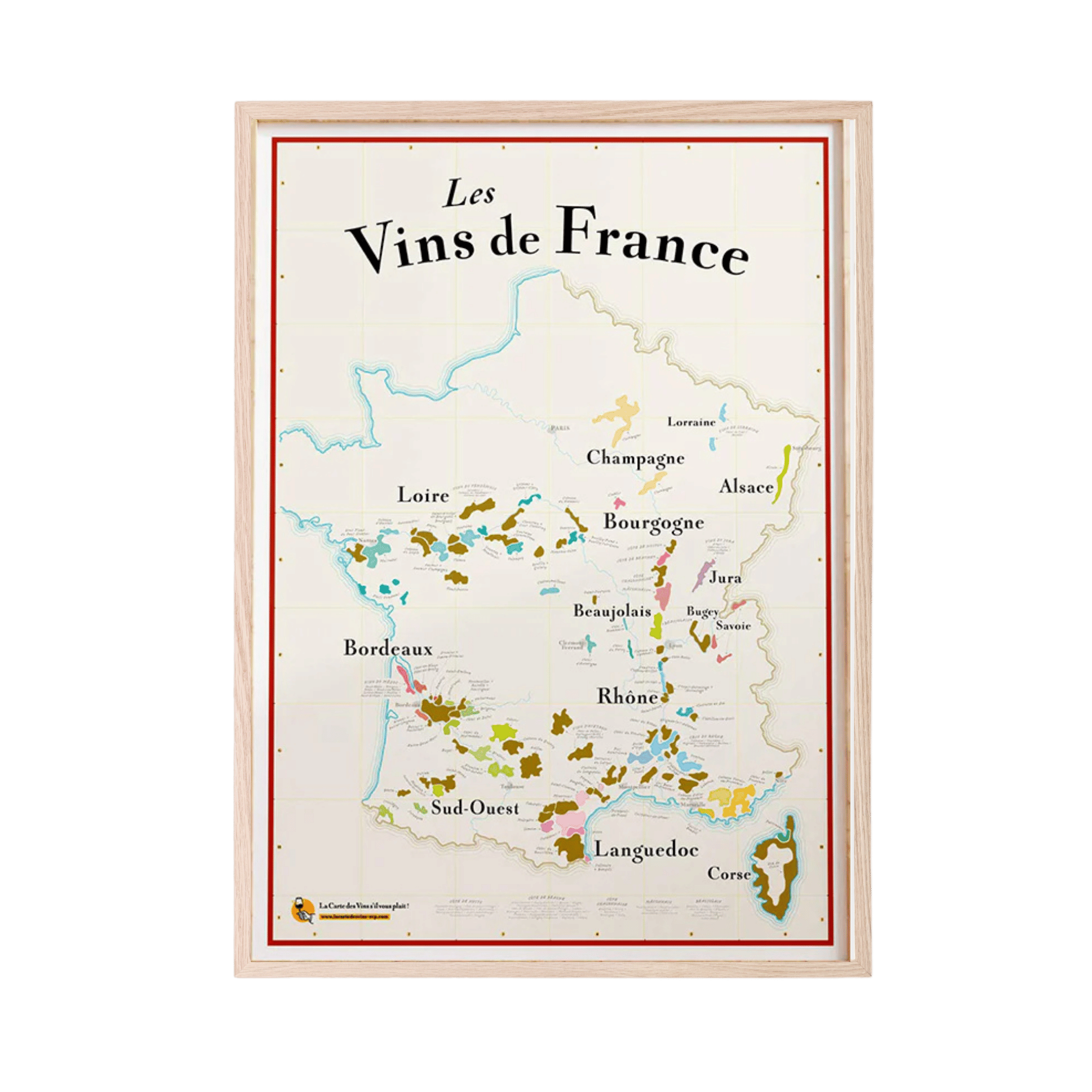

Another highlight is the Riesling Claude made the year he retired. Jelmer gave him carte blanche for his last wine, and it became Ze Riesling. "Ze" is pronounced like the English "the" but with a French twist. A lovely, fresh Riesling style, and unique: this wine was only produced once. Want something a little more mature? We also got to taste the 2002 Riesling Grand Cru Kastelberg. Truly beautiful. Domaine Moritz has vineyards on four Grand Crus: the Grand Cru Winzenberg in the village of Blienschwiller, and three Grand Crus in Andlau: Mönchberg, Kastelberg (pictured below), and Wiebelsberg. So there's so much more to taste. Definitely worth a visit!

More about Alsace?

Guest blogger: Jelle Stelpstra

Jelle Stelpstra started his career as a tax advisor but after 12 years switched to something even more interesting than taxes: wine. Jelle owns the Walsjérôt wine bar in Rotterdam and is a vinologist. At Walsjérôt, you can pour your own wine from over 70 wines.

Share:

A look inside Isole e Olena

A look inside Domaine Hugel