Besides the many classifications, rules, and exceptions to the rules, the region is extremely fragmented. It consists of many small plots of vineyards. This is a relic of the French Revolution. Before that time, most vineyards were owned by the Church, but Napoleon put a stop to that. The vineyards were divided up and auctioned off. Then the first fragmentation began, and this fragmentation was perpetuated by the complex inheritance laws that were introduced.

Inheritance law dictates that property is divided among all family members. But perhaps not everyone wants to become a winemaker? And "just" selling a piece of Grand Cru, while your brother might actually want to make wine from it... Well, those aren't exactly the ingredients for a cozy Christmas, I think.

All this leads to enormous fragmentation. And then you get some bizarre structures. For example, Clos de Vougeot, a 50-hectare Grand Cru vineyard, has no fewer than 80 owners.

So yes, don't assume you've arrived just because you see a well-known vineyard on the label. The merchant or winemaker actually says much more about the quality.

It's difficult, huh?

Terroir is the magic word

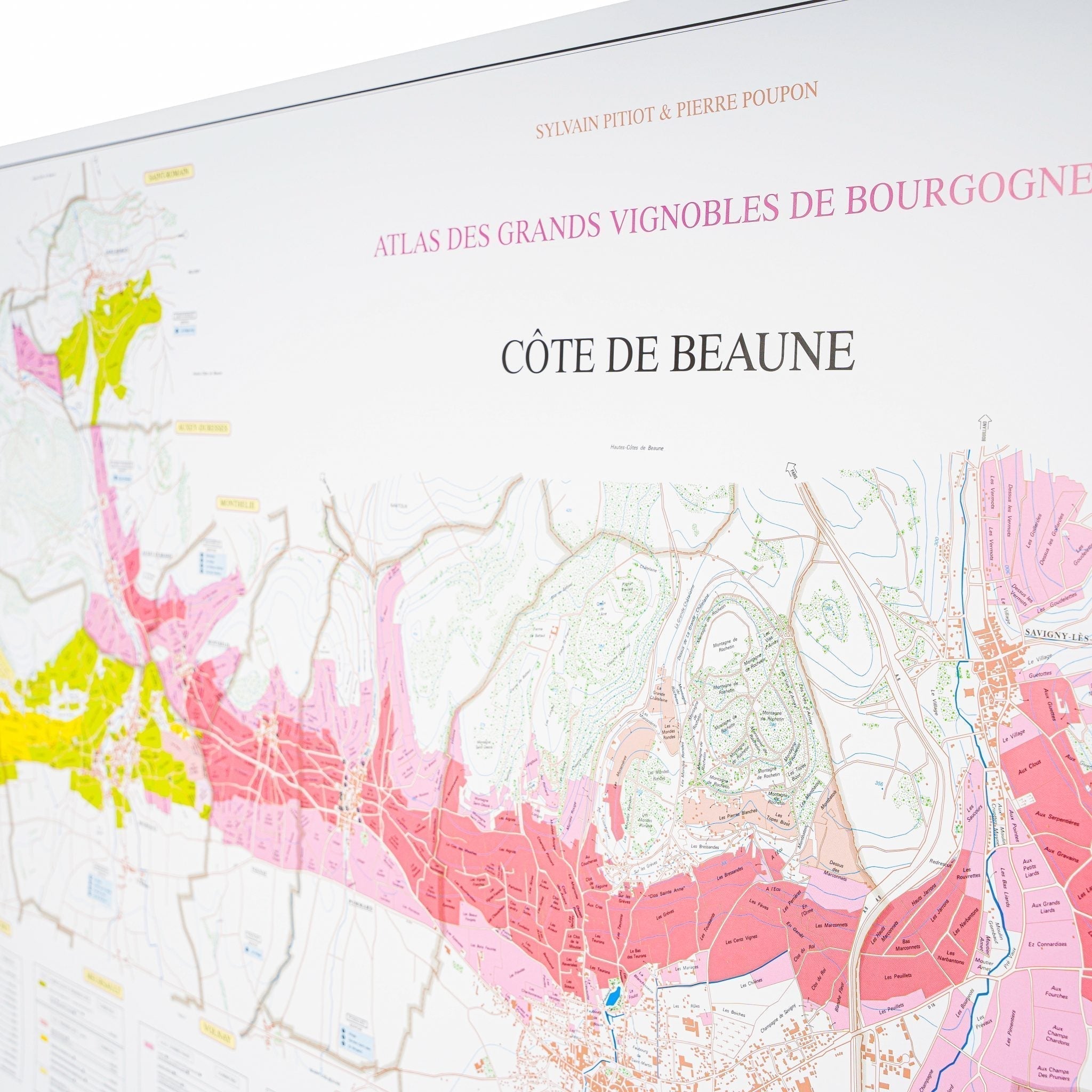

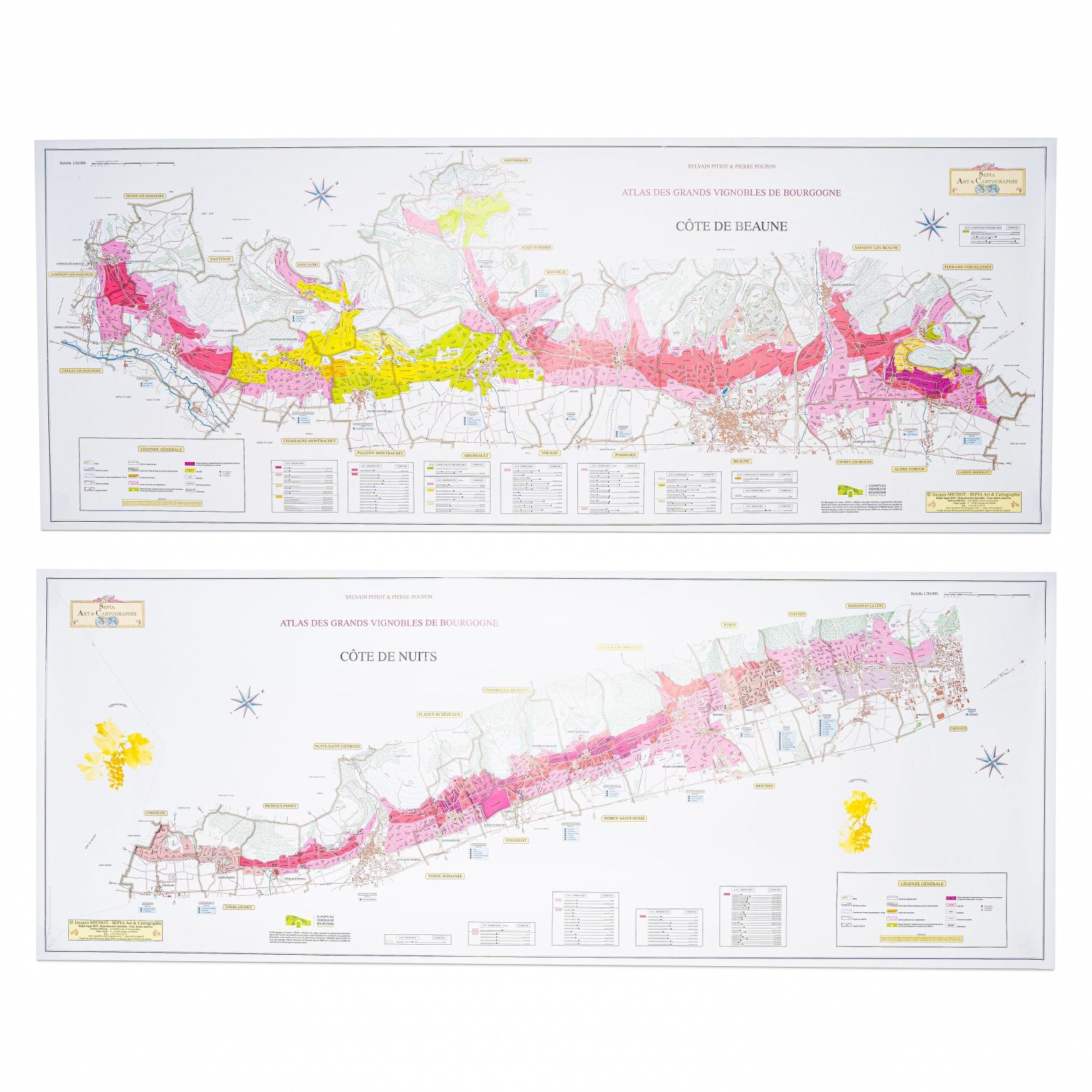

The interplay of soil, climate, vineyard location, and winemaker expertise can be described in a single word: terroir . And that's precisely the magic word for Burgundy. Every square meter can be different.

My WSET instructor recently told me he was having a tasting of several wines from the aforementioned Clos de Vougeot vineyard. He wouldn't even pay €10 for some of them, while others might be among the best in the world. And to think that—in theory—they all come from the same vineyard.

Chardonnay and Pinot Noir

Fortunately, they keep things simple when it comes to grapes. For white, there's Chardonnay, and for red, there's Pinot Noir. Of course, there's a small exception to this rule. The Aligoté grape is permitted under the AOC Bourgogne Aligoté (and AOC Bouzeron). While it has been overshadowed by Chardonnay for years, it's increasingly coming to the forefront.

Aligoté is a bit like the hipster of Burgundy. Gamay is also permitted in Beaujolais for red wine. We all know it from Beaujolais (Nouveau), of course.

Appellations

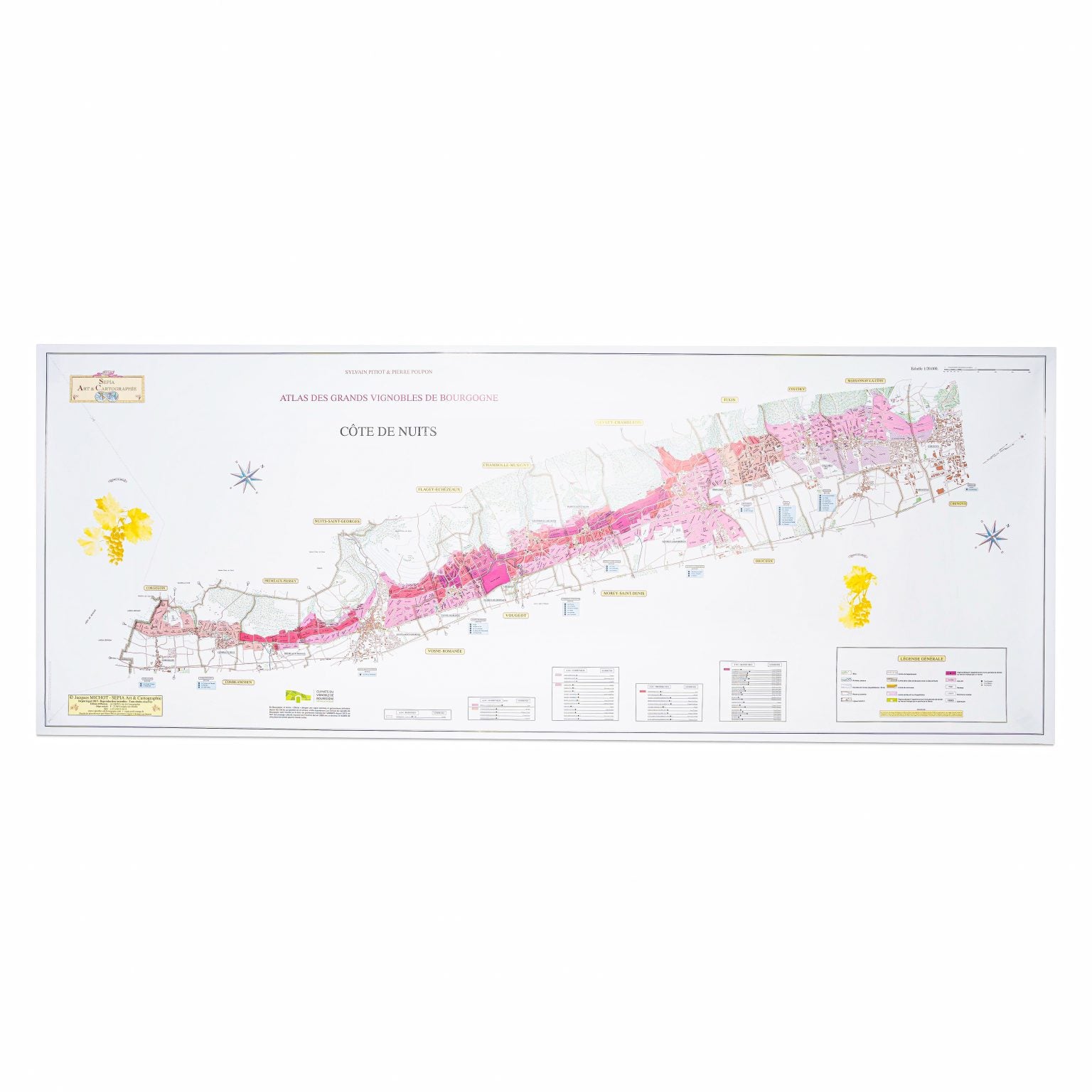

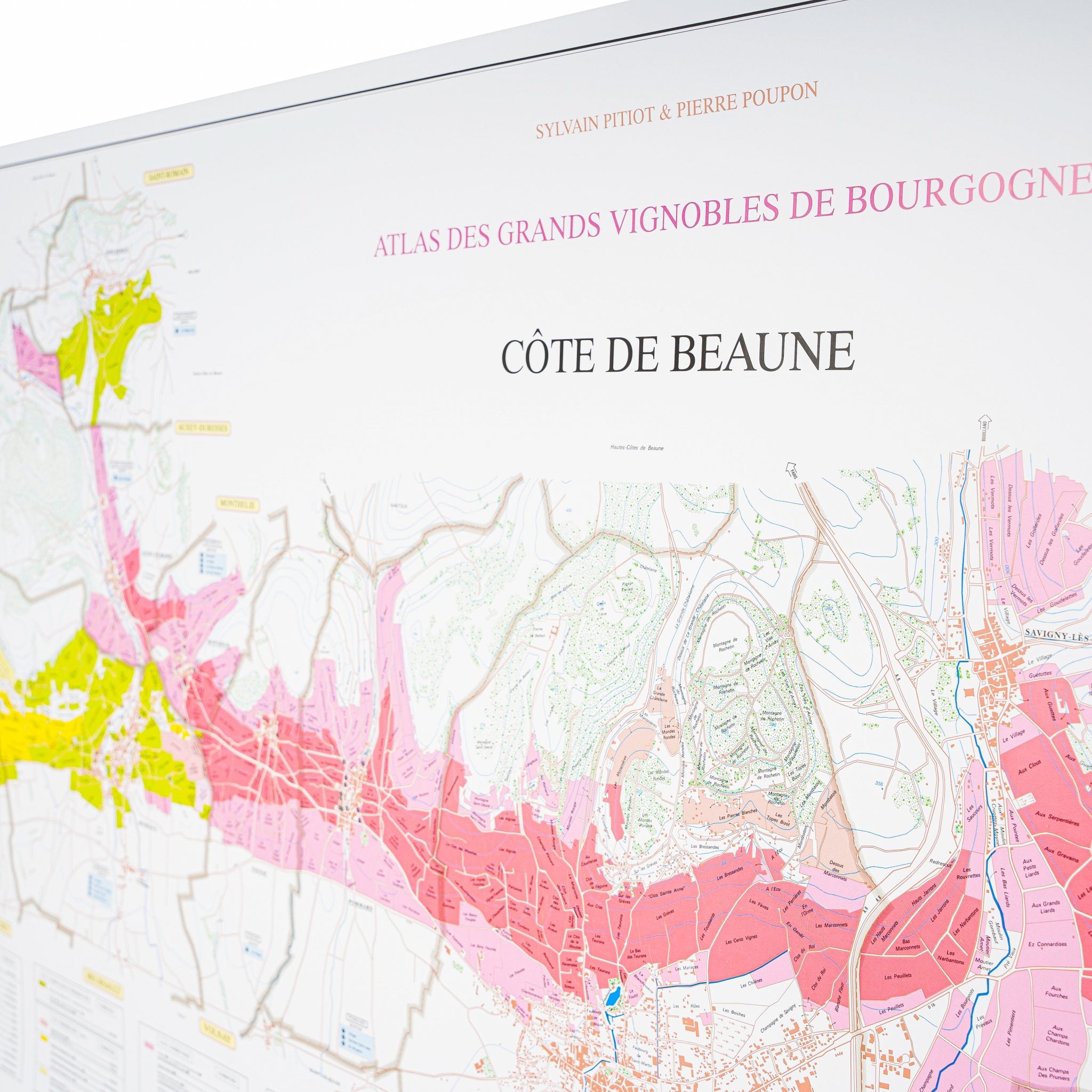

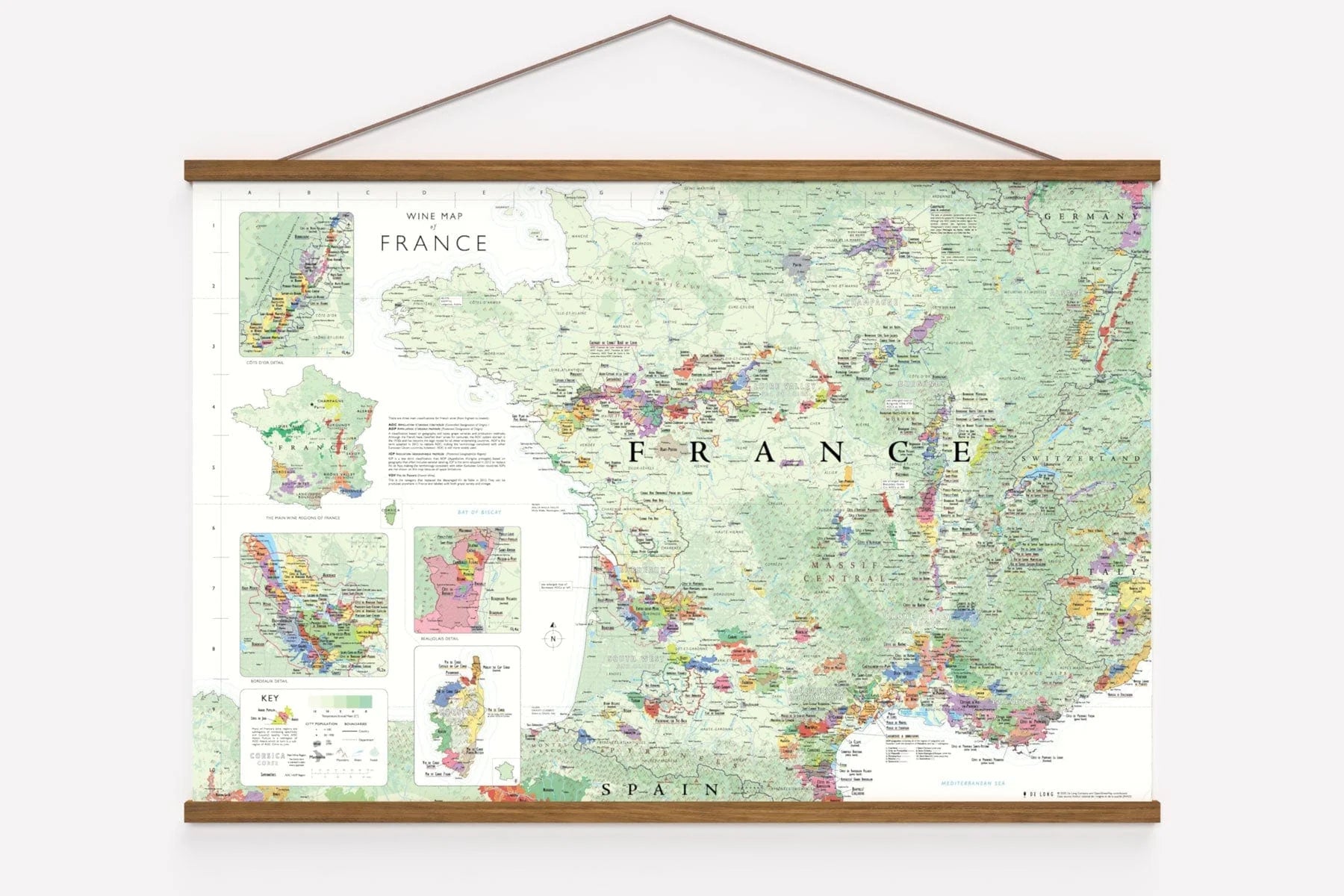

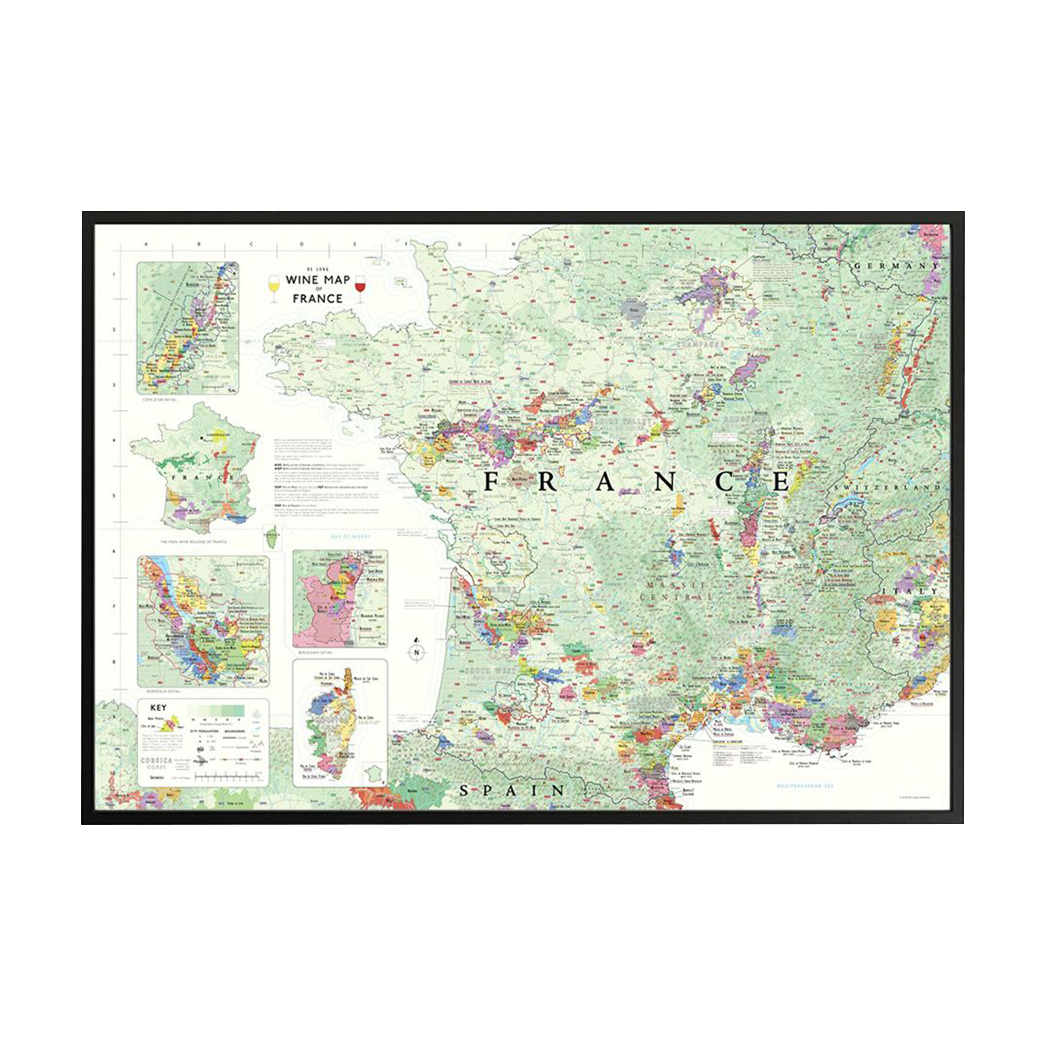

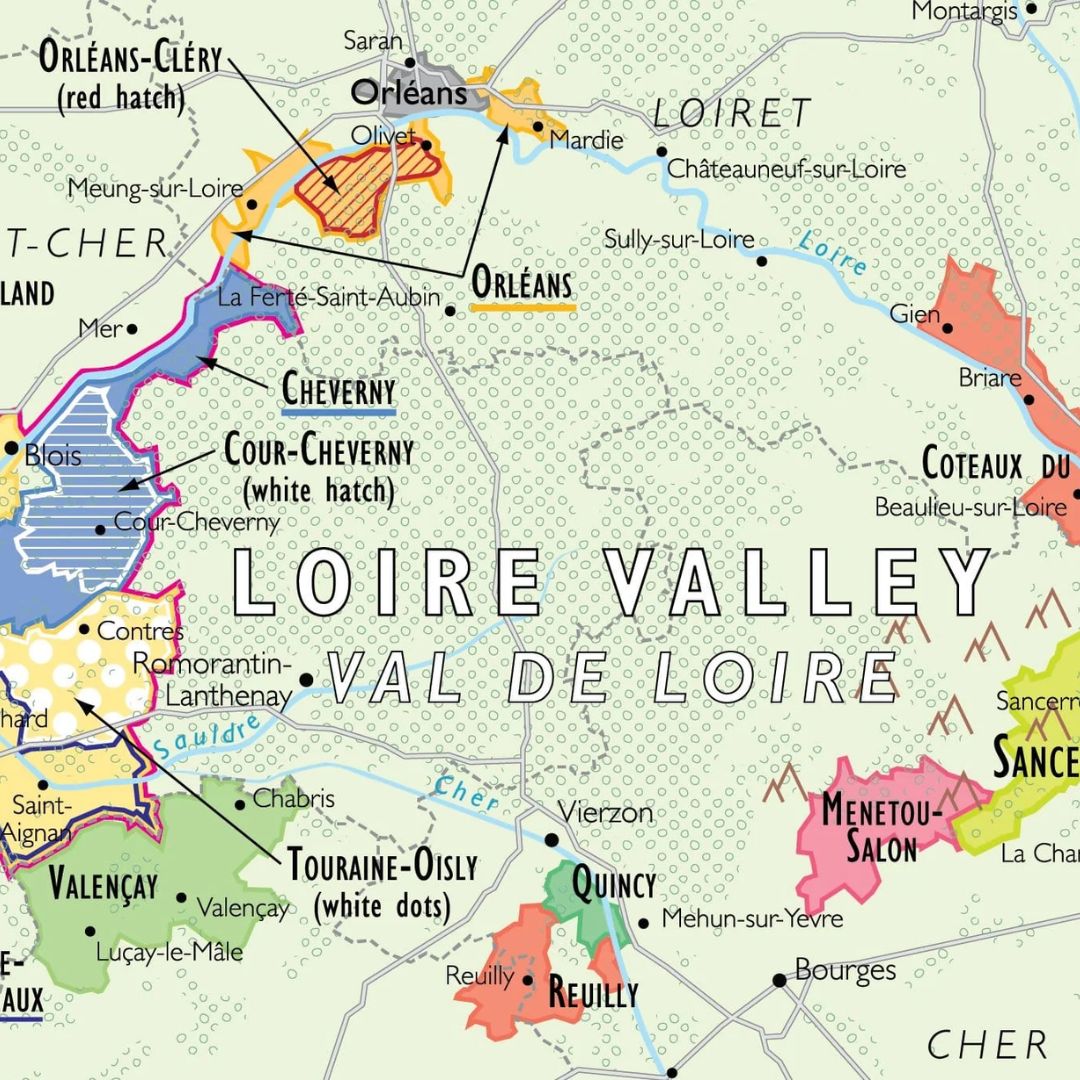

Burgundy is divided into five areas:

-

Côte d'Or consisting of Côte de Nuits (more red than white) and Côte de Beaune (more white than red)

- Chablis for white

-

Côte Chalonnaise for red

- Mâconnais for white

-

Beaujolais for white and red

Classification system

That's not all. Burgundy also has a proper classification system that separates the good from the ugly. This doesn't apply to Chablis and Beaujolais, which have their own classification system. Nice and clear 😉

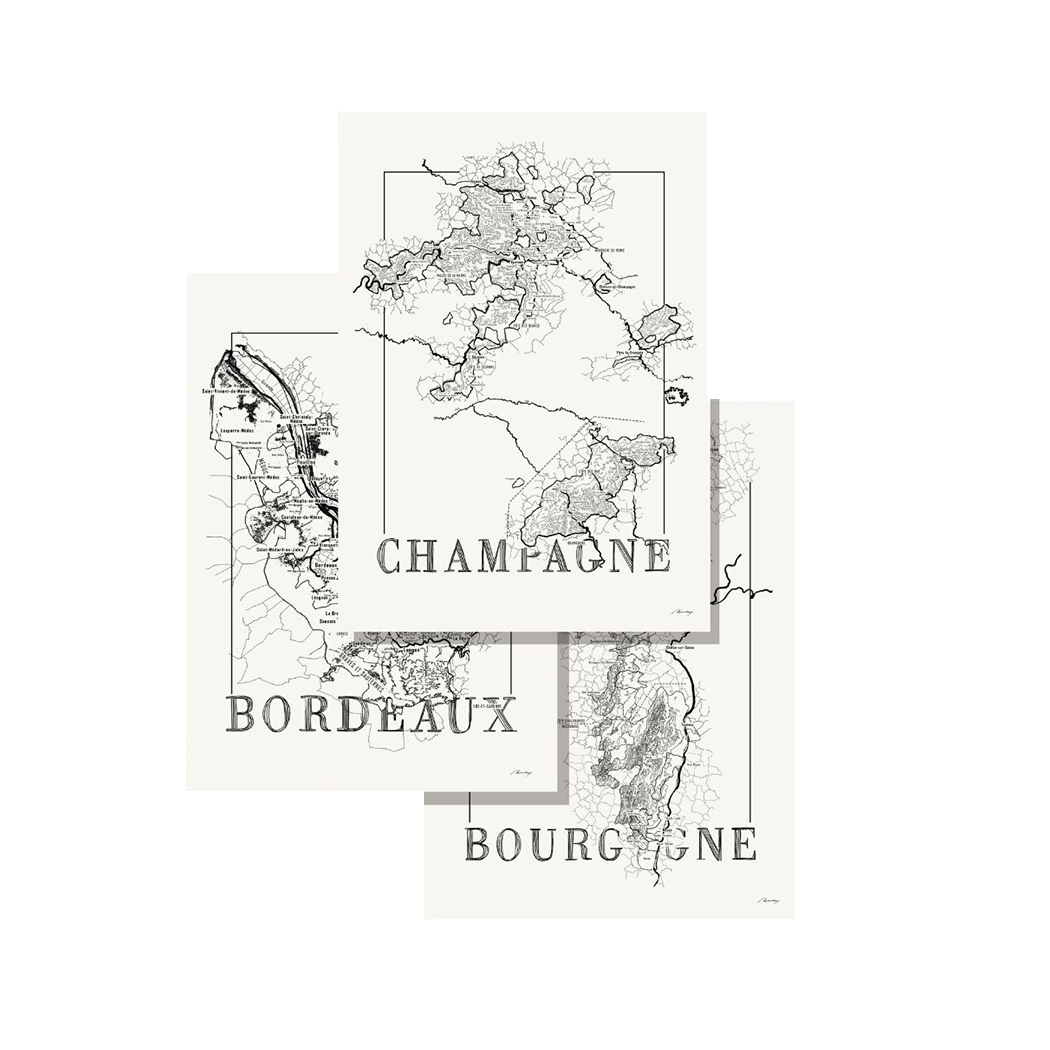

Don't think you understand every French region now. This classification system is exclusively assigned to Burgundy. In Bordeaux, things are very different. Here, the classification system is essentially separate from the appellations. Except in Saint-Émillon, where it is intertwined with the appellation. As you can see, in Bordeaux, there are a thousand rules with just as many exceptions.

Burgundy

"Bourgogne" is printed on the label. These are "regional" wines. The grapes may come from the entire Burgundy region. These grapes are often found in less favorably situated vineyards. The label may say either Bourgogne Blanc (white) or Bourgogne Rouge (red). They are generally lively, fruity wines. Do you enjoy sparkling wine? Crémant de Bourgogne also falls under this AOC.

Villages

A commune is listed on the label, e.g., Meursault. This is a step up and a bit more complex than the one mentioned above. The grapes come from the specific commune listed on the label. A total of 44 communes have their own appellation and are therefore allowed to use their commune name on the bottle, for example, Santenay, Meursault, or Pouilly-Fuissé. That might sound familiar, but don't be blinded by it. The difference in quality between different producers can be enormous. That's why—I'm repeating myself—it's important to check the producer. Also nice: it's permitted to also list the vineyard on the bottle. That's actually reserved for the better wines, the Grand Crus and Premier Crus (see below). Anyway, it's allowed here too, but the vineyard must be written in smaller letters than the commune name. Still following?

Premier Cru

The label lists both a commune and a vineyard, for example, Chambolle-Musigny Les Charmes. We've arrived at the Premier Crus, the second-highest quality designation in Burgundy. There are 635 vineyards that can call themselves Premier Crus. These vineyard plots are called "climats" and produce wines that are generally more intense and complex than commune wines. These wines are often aged in oak. These wines always list the commune name and the vineyard, along with the Premier Cru or 1er Cru designation, for example: Rully 1er Cru La Fosse. The grapes may come from multiple Premier Cru vineyards. In that case, the vineyard designation is omitted, and only the commune name and the Premier Cru designation appear on the bottle.

Grand Cru

A vineyard is listed on the label, e.g., Corton or Montrachet. The best of Burgundy. These are 33 Grand Cru vineyards, primarily located in the Cote de Nuits—sometimes right next to a Premier Cru vineyard. The most famous and also the most expensive wine comes from Romanée Conti. But Montrachet, La Tache, and Corton are also Grand Cru vineyards. Together, they account for 1% of Burgundy's total annual production. Scarcity, of course, comes at a price. These are top wines, meant for aging.

Got some spare cash? Investing in top-notch Burgundy is worth considering.

Want to know more about Burgundy?

Then the website and/or the book ' Inside Burgundy ' might be a nice gift for your next birthday 😉

Or the book "On Burgundy "—a little less reference work, a little more narrative. Wonderful to read with a glass of Pinot Noir in hand.

Share:

Deep down everyone loves gourmet cooking

Methode traditionelle: how is champagne made?