Wine has acidity, we all know that. Just think of the last time someone poured you a Riesling or Sauvignon Blanc. Some love it, others hate it. Some grape varieties produce wines with more acidity than others, and of course, origin plays a role as well.

Where do those acids actually come from, and do they even have a function? I dove deep into the books, and it turned out to be a remarkable feat of chemistry. Don't worry, I've translated it for you into plain language. Speaking of translations, some words don't seem to exist in Dutch. So you'll come across an English word here and there.

How do you taste acidity in wine?

Acids stimulate saliva flow. When we drink wine (or other acidic beverages), the pH in our mouth drops. This means it literally becomes more acidic in our mouths. The body's response is to lower these acids by "diluting" them with saliva to a more neutral pH. The more acid, the more saliva. When we taste wine, we quickly focus on tannins with red wines and forget about acid. With white wines, on the other hand, it's often the first thing we notice. The way we experience acid varies with each type of wine. Take, for example, the "tight and crisp" acidity of a Riesling versus the "ripe and round" acidity of a Sémillon.

Sometimes the amount of acid we experience in wine is masked by sweetness. Think, for example, of the famously sweet Sauternes from Bordeaux or a Riesling TBA. Sweet as sugar, but if you pay close attention, also incredibly acidic. It's strange, really, that these two contrasts exist in a single wine. The acidity prevents the wine from being cloyingly sweet and keeps it drinkable. That's what we call balance. Chill that second bottle!

Want to read more? Check out this article from winemag.com and, of course, the fantastic book Beyond Flavour .

Can you measure acids?

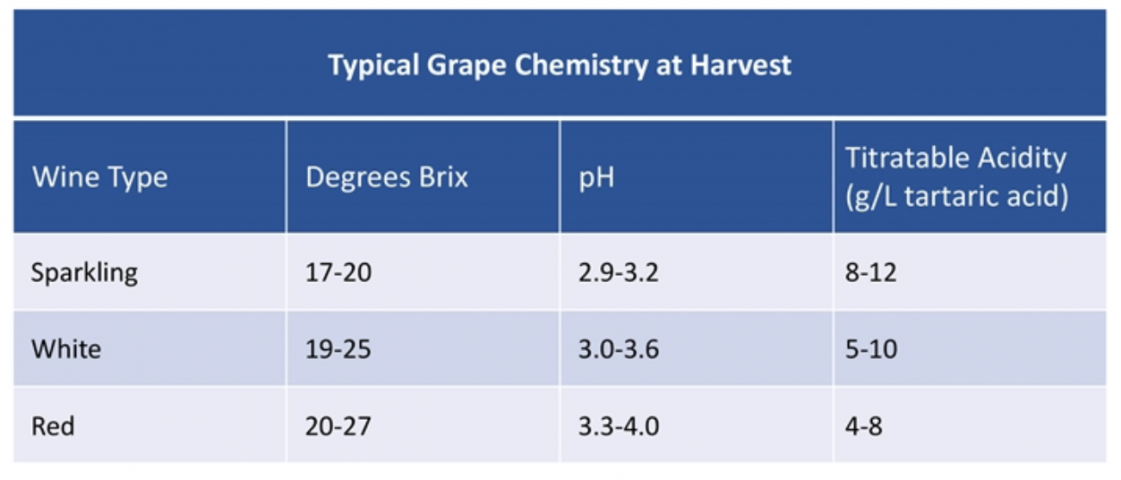

When we talk about acidity in wine, we're essentially talking about two things: pH and total acidity, often expressed as total acidity (TA) in grams per liter. Most wines have between 4 and 9 g/l of acidity. Exceptions, such as sparkling wines, are often higher in acidity. Some producers are very open about these measurements and include them on their technical data sheets.

Total acidity is a collective term for all the acids naturally present in grapes. There are hundreds of different types of acid, but the most important are tartaric acids, citric acids, and malic acids. Total acidity is difficult to measure, but colloquially, it's used to indicate the level of acidity experienced/perceived.

pH, on the other hand, isn't about grams per liter, but rather the "volume" of acids. So, how well do you taste them? Water is considered pH neutral (pH 7), on a scale of 1 (extremely acidic) to 14 (very soft). Anything higher than pH 7 has a low acidity (g/l), while anything with a low pH has sky-high acidity. Confusing, I know.

White wines have an average pH of 2.0-3.5, and red wines usually range from 3.3-3.8. Note that the pH scale is logarithmic. This means that a wine with a pH of 3 is perceived as approximately 10 times more acidic than a wine with a pH of 4. What's the point?

Want to read more? Check out this article from Guildsomm.

Where do acids come from?

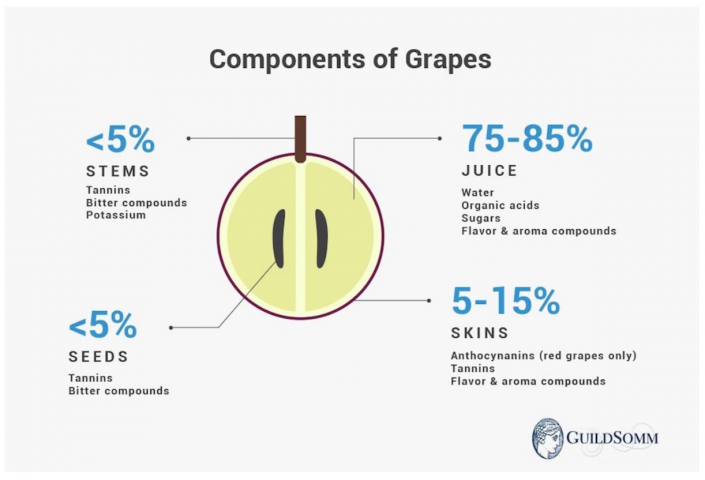

When we talk about acids, we can distinguish two categories: acids from fermentation and the natural acids I just mentioned: tartaric, citric, and malic. Natural acids primarily consist of tartaric and malic acids, accounting for approximately 90% of the total. Tartaric acid is the most important component of the acid mix and is responsible for the stability of wine's color, among other things.

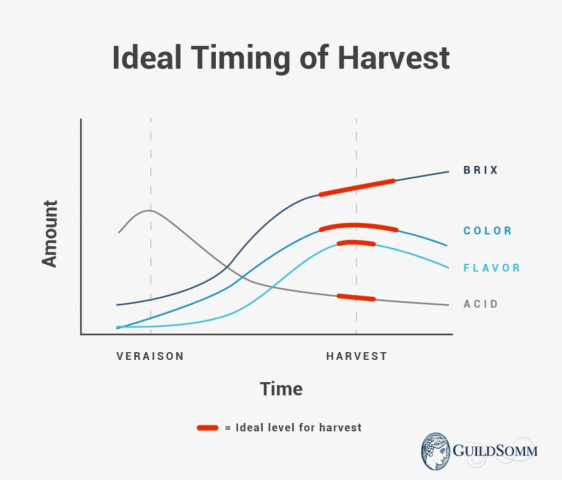

Malic acid, the name comes from "malum," the Latin word for apple, the fruit in which researchers first discovered this type of acid. Malic acid is present in almost every type of fruit. During the grape's ripening process, which breaks down acids, it's the last acid to be broken down. Once all these acids are gone, the grape is considered "overripe."

Citric acid, logically named after the acid often found in citrus fruits. In grapes, it's present in small quantities, about 1 to 20 of tartaric acid.

A plant "breathes" as part of photosynthesis, the process of converting sugars into energy. This energy is used by the roots, shoots, grapes, and all other parts of the plant. This process stops just before veraison, the moment the grape changes color and ripening begins. At that point, the sugars are no longer used as fuel but are stored in the grape as sucrose. The plant must, of course, continue to work, and at this point, it switches to malic acid as its primary fuel source. This explains why we see sugars in the grape increase and acidity decrease during the ripening process.

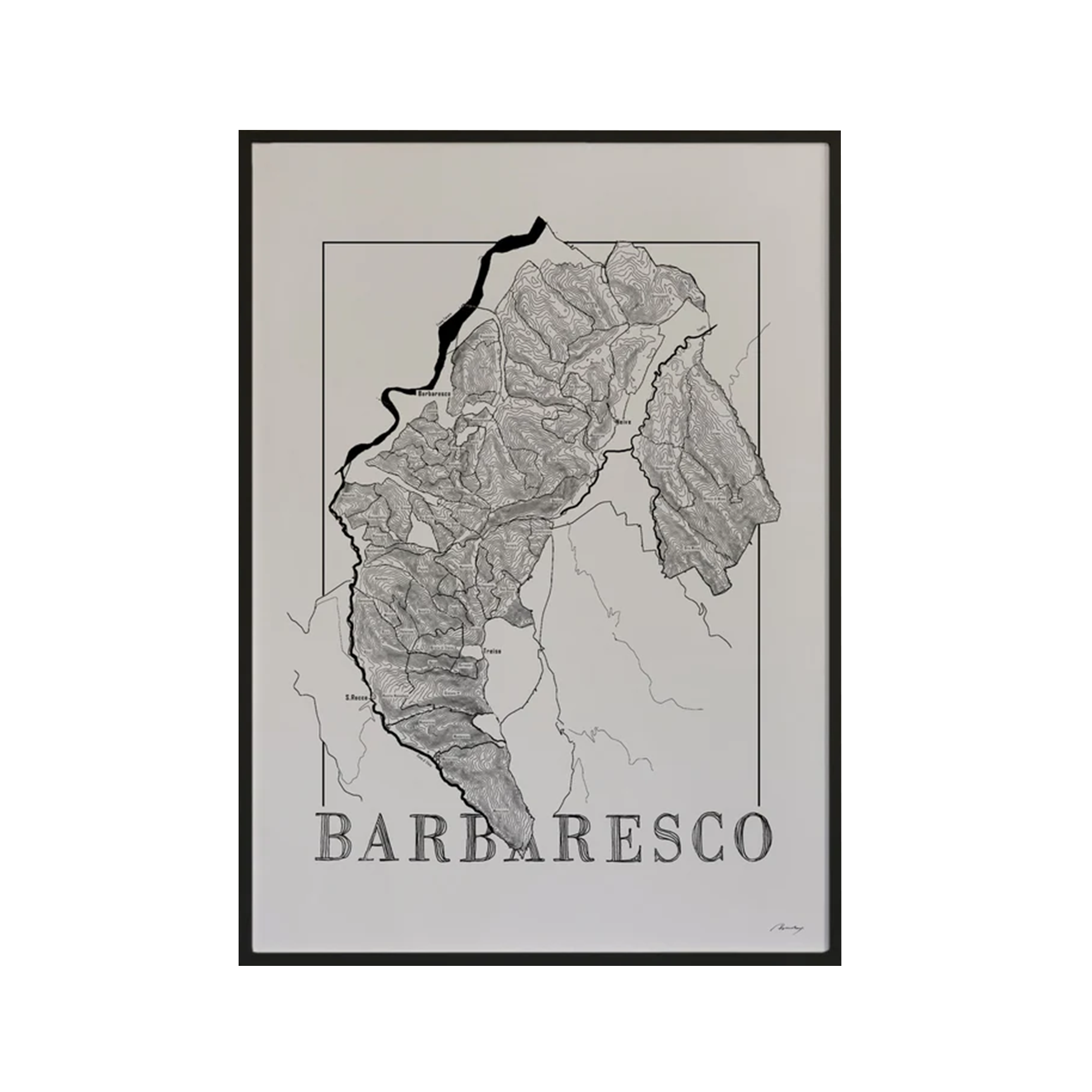

Acids and soil

The soil influences the acidity of grapes. It sounds strange, but it's actually quite logical. The water absorbed by the vine's roots is full of minerals, including potassium. Potassium is essential for photosynthesis and helps neutralize acids and raise the pH. Too much potassium in the soil, therefore, causes grapes to lose their acidity. Sandy soils, for example, contain much less potassium than soils with a high clay content.

Acids and climate

In short: the cooler the climate, the more acidity, and the warmer the climate, the less acidity. It's a simple rule of thumb, with undoubtedly hundreds of exceptions. Wines from warm regions can also be high in acidity, for example, if they're grown at high altitudes or experience cold nighttime temperatures? Yes, that's all true!

The plant's "respiration" we just discussed depends on temperature. The higher the temperature, the more respiration. In warm climates, the amount of malic acid-based respiration is higher, resulting in lower acidity in both the grape and the final wine. Wine respiration occurs in the absence of light. Respiration slows down during cold nights, while sugar production can only occur during the day when there is sunlight. This preserves the acidity.

Want to read more? Check out this article from wordonthegrapevine.co.uk or this one from Guildsomm .

What is the function of acids?

Besides the fact that acidity in wine can naturally be delicious and balance the wine, it also has other functions. For example, it also affects the color. Did you know that red wines with high acidity usually have a brighter red color? The low pH creates a kind of red sheen. Wines with a high pH, and therefore lower acidity, have a more blue/purple hue. We also associate that purple hue with young wines, but apparently, it also has to do with acidity. Furthermore, acidity protects against oxidation. So you can assume that wines with a long aging potential often also have higher acidity.

The second is stability—we all seek it in our lives—and in our wines as well. To make wines stable, winemakers add sulfites in varying amounts. Dosages can be adjusted, and this is a hot topic, especially in the natural wine world. Sulfites (SO2) bind to acids. The more acid in the wine, the less sulfites are needed to protect it from bacteria. If the wine is stable (or more stable), it is also more suitable for bottle aging. All positive!

At least, if it is in balance, because let's be honest: a wine with only acids is not pleasant to drink either.

That's it for today. Part 2 will be online soon, in which I'll explain more about adding acid and deacidifying wine. Stay tuned ;-)

Share:

Questions and answers about alcoholic fermentation

A wine fan in Tenerife