The moment you thought would never come. I'm standing on the doorstep of Le Pin, a tiny but very well respected A winery in Pomerol. All sorts of things are racing through my mind, and one image just won't go away. About six years ago, I was here too—well, not at Le Pin, but in the region. It was my first real wine vacation. We (my friend Hanneke and I) rented a bike and cycled past the grand and small wineries of Bordeaux, full of admiration. Did I ever expect to knock on this door? Never in a million years.

Did I expect to quit my job and live off Le Club? Not at all. It's amazing how life can turn out, isn't it? Just realize that anything is possible. If you're willing (and willing to work hard, because hey, it doesn't just happen). *End of drama*

An old saying goes that everyone can be reached within six handshakes. I now firmly believe that too, even though I only needed one for this epic visit. Earlier this year, I took a lesson from Fiona Morrison MW during WSET Diploma Course . I don't usually ask for anything, but that day I was determined. “Hey Fiona, I'm in Bordeaux in October, would it be possible to visit?” And so this epic visit came to pass.

Grand and captivating

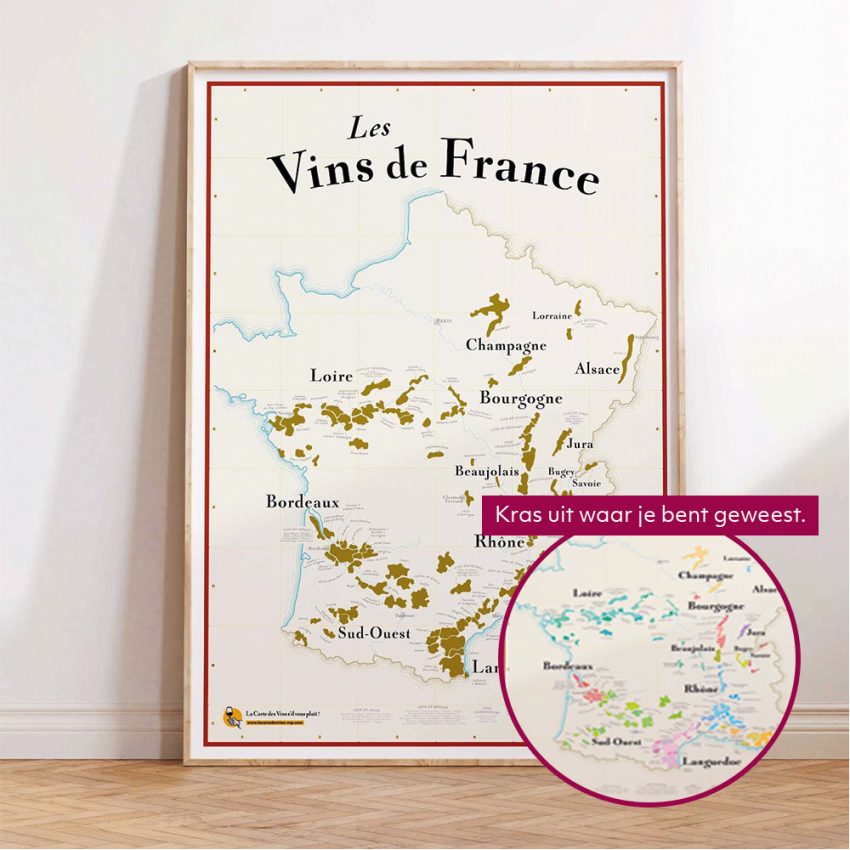

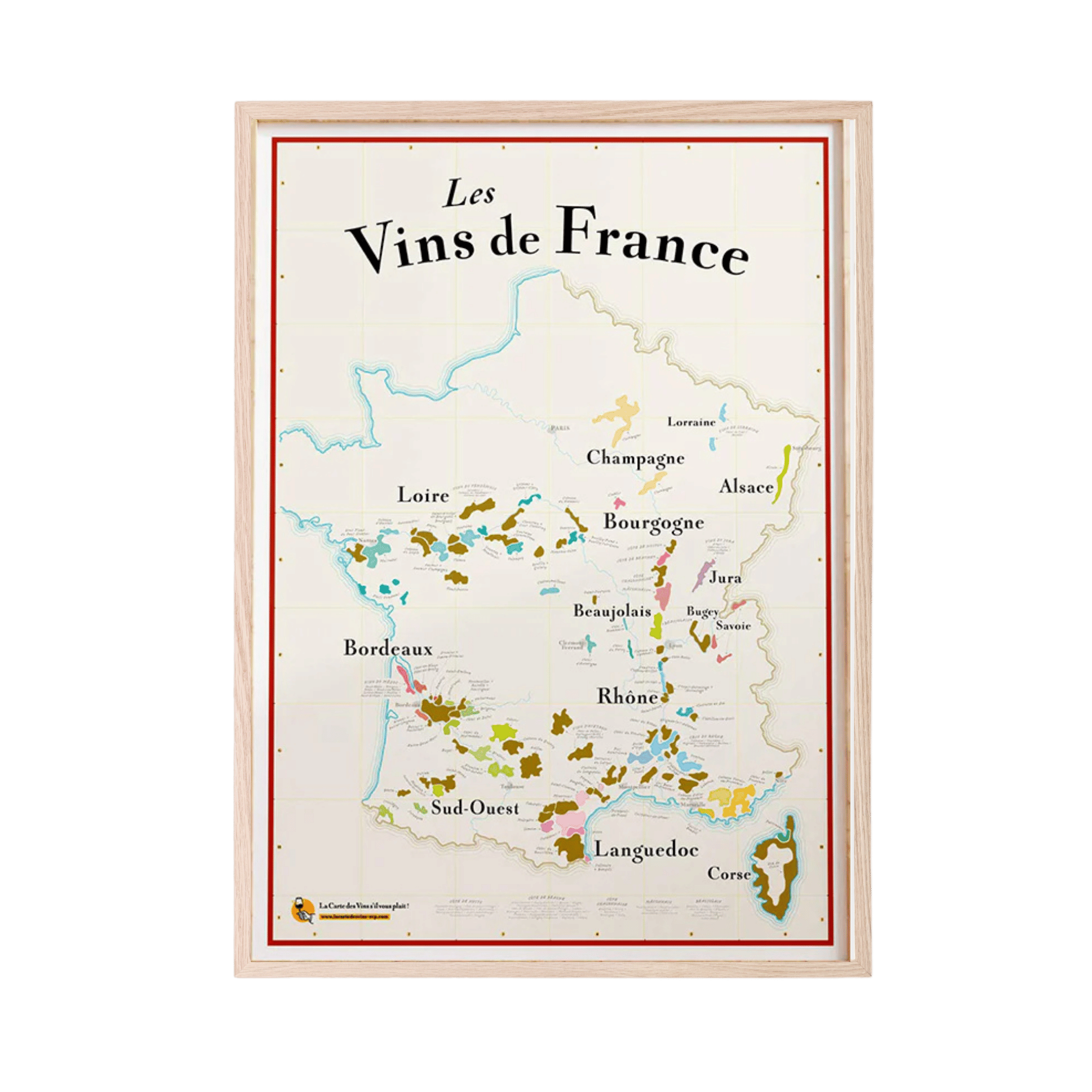

Don't expect grand and impressive châteaux in Pomerol. For that, you'll have to go across the river; the left bank is full of them. But on the right bank, the Pomerol and Saint-Émilion side, it's much more rustic and charming. The Le Pin winery isn't imposing either, but it is classic and elegant. I can tell you all about it now, just like the wine, but more on that later.

Upon arrival, we were warmly welcomed by Fiona Morrison and her husband, Jacques Thienpont. Fiona had to get going immediately, as the harvest in Saint-Émilion, where they also have a chateau, was in full swing. We were in good hands with Jacques, the owner/winemaker of Le Pin and proprietor of Thienpont Wine, a major wine merchant in Belgium. A nice bonus: we could speak Dutch. We went up to the rooftop terrace where Jacques told us more about Pomerol.

The magic of Pomerol

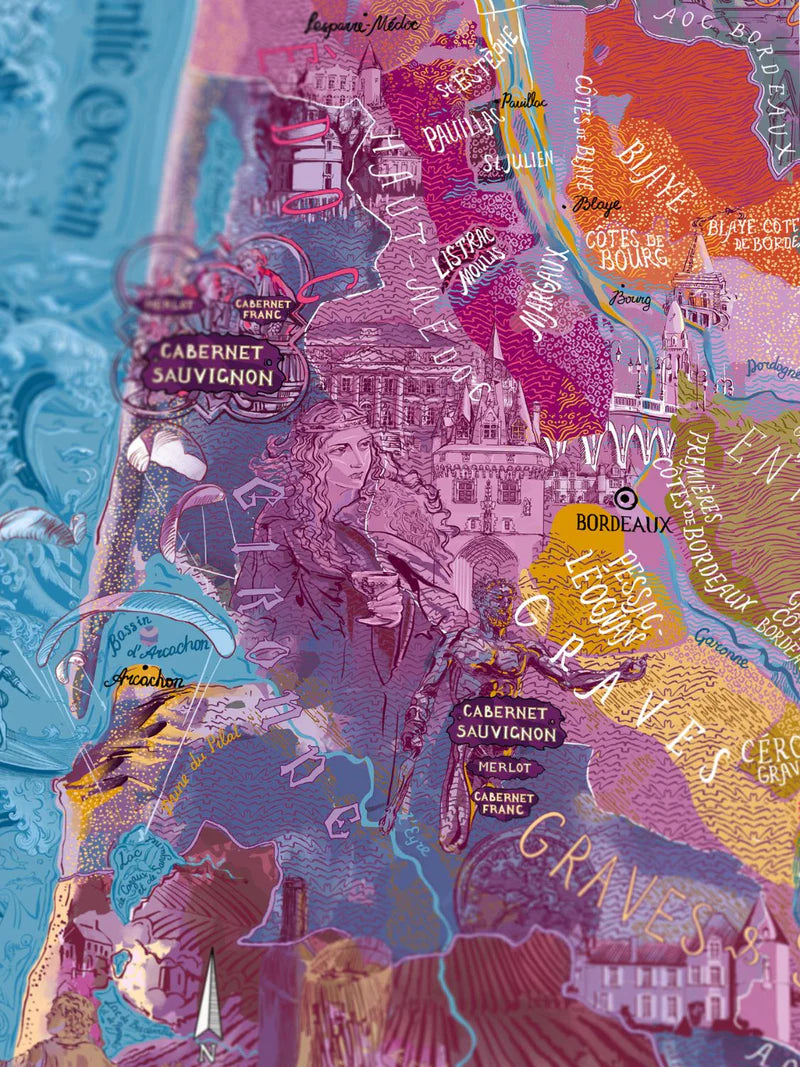

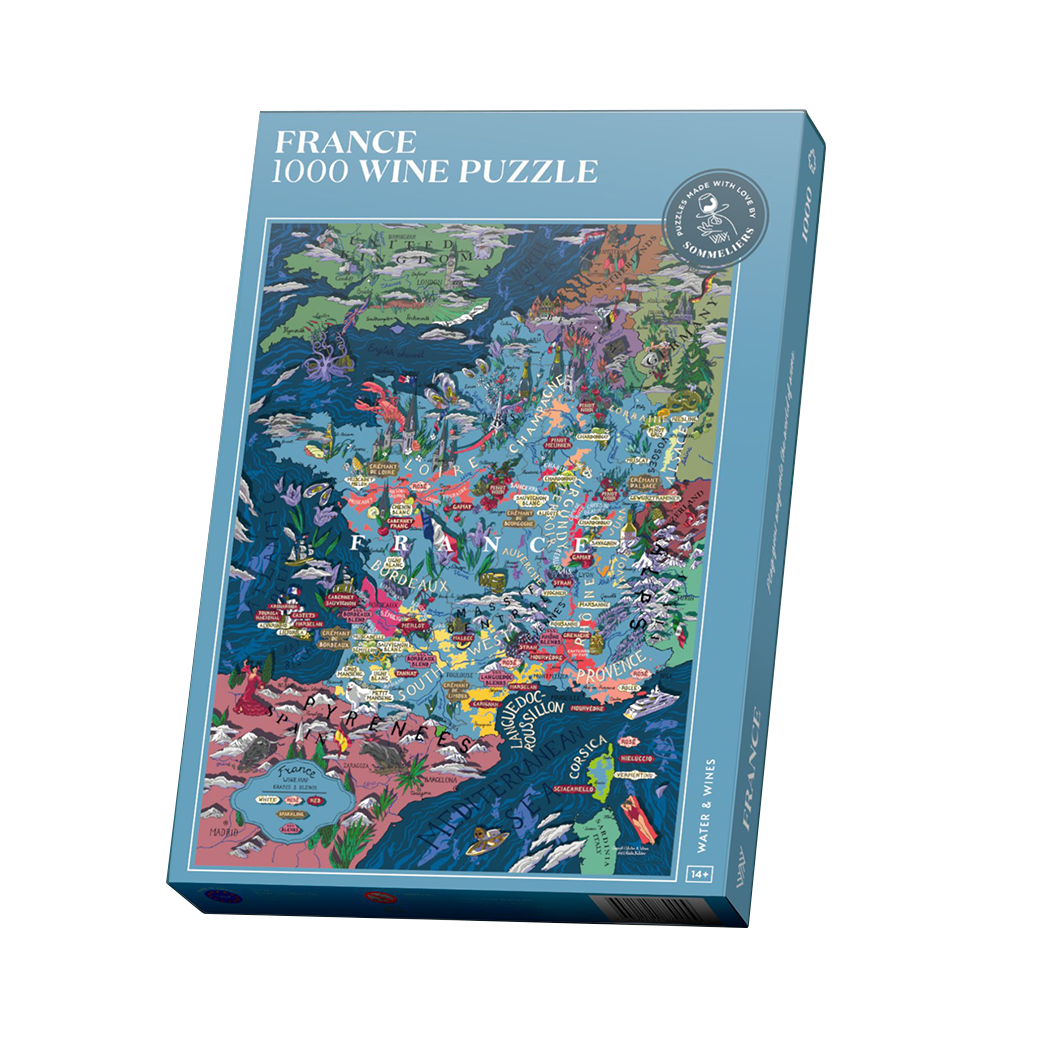

Bordeaux boasts 115,000 hectares of vineyards, more than all of Germany combined. Pomerol's share of this is small. The appellation comprises only 800 hectares in total. When Jacques bought the property, there were 180 landowners; today, there are around 120. "Most owners own only one or two hectares," Jacques explains. The area is fragmented. And incredibly expensive, because it's scarce. The largest chateau is Chateau de Sales, with 47.5 hectares. The most famous chateau, Chateau Petrus, covers twelve hectares and is practically opposite Le Pin; we can see it from the roof terrace. Le Pin started with one hectare and now has three.

Unlike the rest of Bordeaux, where classifications are everywhere, Pomerol doesn't have one. It's AOC Pomerol and that's it. The advantage is that everything is high quality. I've yet to encounter a bad Pomerol.

At first glance, the landscape seems quite flat, but there are some elevation changes here and there. The best vineyards come from the so-called plateau, which reaches an altitude of 40 meters above sea level and accounts for only 25% of the total production. This is where the top wines originate. Clay is the common denominator, but that's about it. Petrus has a thick layer of clay, which is located high up. Le Pin has more sand and gravel, the clay being much deeper. It's said that the wines from Petrus are often a bit firmer, while those from Le Pin are more elegant. I'll come back to this after I've tasted Petrus.

About Le Pin

Le Pin was born in 1979 when Jacques Thienpont purchased a one-hectare plot in Pomerol. He had to pay 1 million French francs at the time. This wasn't entirely unexpected. The Thienpont family has a long history with wine. Jacques' uncle, owner of Vieux Château Certan, located roughly between Le Pin and Pétrus, had been eyeing the plot for some time, considering buying it and adding it to Certan if it ever came on the market. But the family found it too expensive. Jacques eventually bought it and renamed it Le Pin, a reference to the pine tree across from the winery.

The magic of Le Pin naturally begins in the vineyard, where the Merlot vines are neatly arranged. Here and there, we see a vine with a blue ribbon. These are older Cabernet Franc vines. They are not used in Le Pin's wines, but are harvested separately and sold as wine to other growers in Pomerol. The three hectares are closely supervised by Jacques's nephew, who now runs Vieux Château Certan, as Jacques himself is usually in Belgium. They work organically as much as possible, but are not certified.

"It's my hobby here. Normally I'm in the wine trade in Belgium."

You'd think those three hectares would be harvested in no time. But no, they take their time. This year, the harvest took 14 days. “Not before,” says Jacques. “In the past, everything was harvested at once, but now we work much more selectively.” They go into the vineyard with a tractor to measure the moisture content of the leaves. This is mapped and shows exactly where the pickers should begin harvesting. Moisture is a good indicator of the grapes' ripeness. In practice, this means they harvest for an hour one day, not the next, and then two hours the day after that. They work with local pickers who are on call daily.

This year, 2019, was a good one. The rains fell on time. Some were harvested before the rains and some after. The pre-harvested grapes had a high sugar content and therefore a high alcohol potential. That's why they left some of the grapes hanging. The grapes would absorb some of the moisture, lowering their sugars. The total alcohol potential would then be 14 to 14.5%. High, but acceptable. That's different from twenty years ago, when they still had to add sugar to achieve a minimum alcohol content. Now, the opposite is true. Filtering machines that remove alcohol from the wine have already been spotted in Pomerol (not at Le Pin).

Incidentally, the weather isn't always cooperative. In 2003 and 2013, the harvest wasn't good enough for Le Pin. Jacques decided not to make any wine and sold the grapes to other growers in the region.

"Since 2015, we've been feeling the effects of climate change enormously. Previously, we could still use indigenous yeast cells—the yeast cells that grow on the grapes—but that's no longer possible. These indigenous yeast cells don't reach 14-15%. So now we have to add yeast."

The harvest is visible in the cellar, where fermentation is in full swing. Le Pin is made entirely of Merlot, but I count at least eight tanks. Even though it's the same grape, ripeness can vary, so the grapes are fermented separately. Fermentation, including skin maceration, takes three weeks. Malolactic fermentation then takes place in new 225-liter oak barrels. This takes about two months, so by early December, malolactic fermentation is complete, and the 18-month oak aging begins. Only then is the wine blended.

A preview of Le Pin 2018

"Tasting the wine of '18? Or is it too early?"

Uh. It's never too early for Le Pin! Is this really happening? I'm completely overwhelmed. Only 6,000 bottles of Le Pin are made each year, the whole world wants it, and the price ranges from €4,000 to €12,000. Is this real, or am I dreaming?

"Which barrel do you want? You can choose."

Fifteen minutes ago, Jacques told me that Robert Parker comes here to taste the wines every year. To be honest, I didn't ask if Parker still comes. His website is now run by other tasters, but perhaps he'll still cherry-pick and taste a few houses himself. Parker, Jancis Robinson, Tim Atkins—they've all been here.

And now I'm standing there, and in my glass is Le Pin from the middle barrel. It's magnificent. It's elegant. More concentrated than any other wine I've ever tasted. Even though it's still very young, the tannins are already so ripe and soft. No words. I'm speechless.

3 Questions You Just Want to Ask

What's your favorite wine region outside of Pomerol?

Piedmont. The Burgundy of Italy.

What was your best year?

“1994 and 2001.”

What is the most difficult thing about making wine?

"Nothing. There's nothing complicated about it. It's just picking the grapes, putting them in a vat, and waiting for fermentation to begin."

And with those wise words I close.

What a special visit. Jacques and Fiona are incredibly friendly, approachable, and kind. With so much success, you might expect someone to get carried away, but nothing could be further from the truth. We could ask Jacques all the questions we wanted, and Fiona was already behind the sorting table at the family's other chateau: Chateau L'If in Saint-Émilion – which we'd also visit later that day.

Share:

The Reveur's Vineyard

Affordable enjoyment: bring on that Bourgogne Côte d'Or!