A promise is a promise: when I last year 10 favorites from Beaujolais wrote for I concluded "Le Club " with the words "to be continued." That top 10 wasn't complete. Impossible. But no matter how extensive that list ultimately becomes, it will never be complete, because so much is happening there, south of Burgundy. Boring négociant wines are making way for trendy, new natural wines from emerging producers. The ever-warming climate is driving a changing wine style, and many winemakers in Beaujolais, particularly the crus, are striving to produce true terroir wines that rival the pricey Burgundies.

The ten crus

It once caused me a lot of headaches: memorizing the ten Beaujolais crus. Up to nine, no problem. But that tenth, which one was that again? Moreover, the missing one was often of varying nature. Chénas, for example. Chiroubles. Or Régnié. Perhaps not the most glamorous crus either. But is that justified?

Most of the crus received their AOC status in the 1930s, with the main exception of Régnié, a hamlet that was only promoted to cru in 1988, often jokingly referred to as the youngest named.

Today, there are 10 crus in total, each with its own distinct character. However, it's often very difficult to pinpoint the specifics of character. Open any wine book, and you'll undoubtedly read that St. Amour wines are characterized by their romantic finish and Fleurie is supposed to smell of flowers. This isn't surprising, as in practice, it's very difficult to determine the character of the 10 crus, let alone distinguish them. Generally speaking, a cru is a cru because the combination of microclimate, soil type, and vineyard location are among the best in Beaujolais. But even within the crus, there are terroir differences. And so, sometimes, it's impossible to pinpoint them.

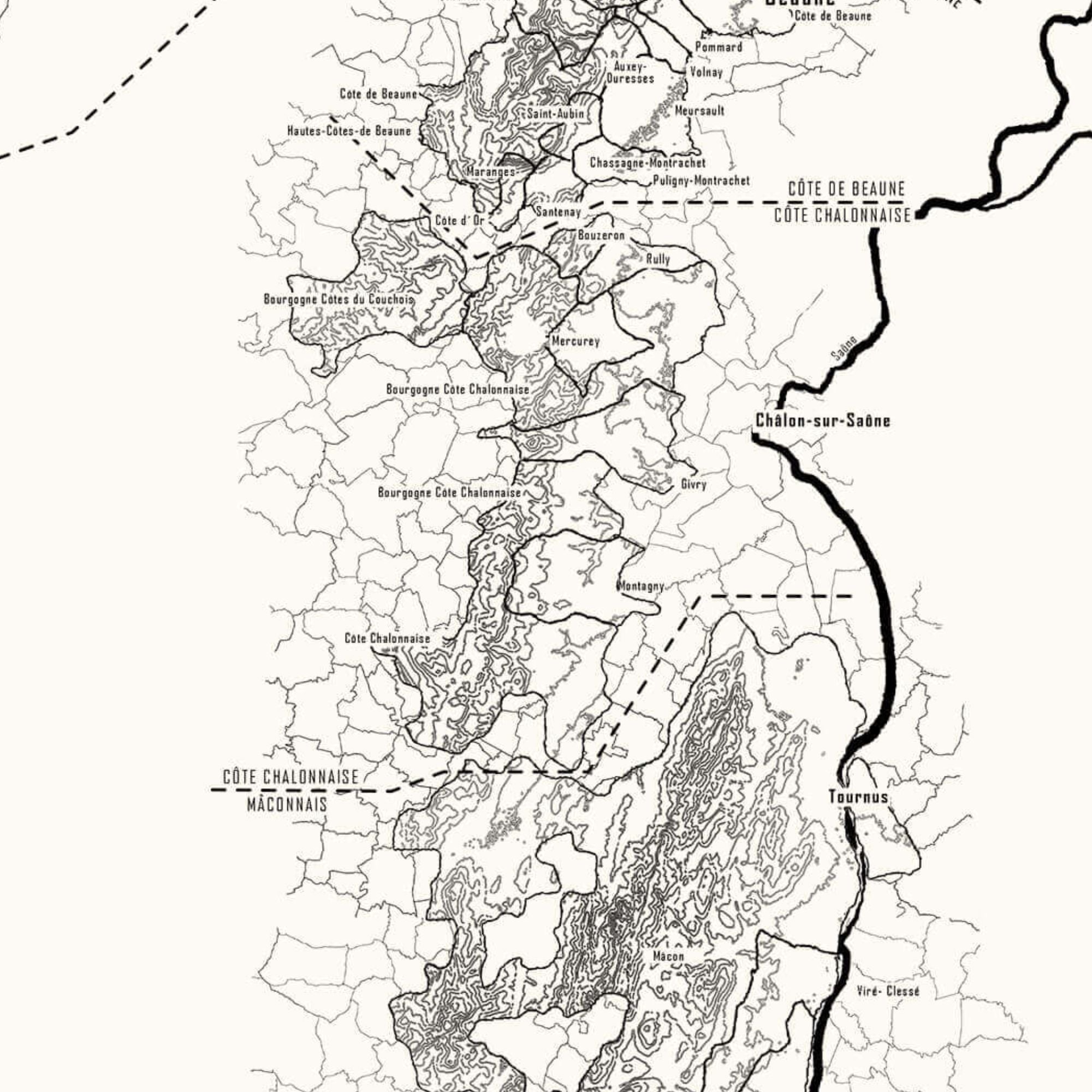

Moreover, many producers have their own ideas about what a typical Morgon or Brouilly should taste like. And global warming is also exerting its influence in Beaujolais. So the differences are significant. And that forces us to generalize. But those differences do exist, although it's best to look at the differences in the terroir of the villages and their vineyards. Moulin-á-Vent—the powerhouse—for example, has a fair amount of manganese in its soil, which creates a kind of natural yield limitation. This often results in a concentrated style of Gamay. Régnié has a lot of pink granite. And the vineyards of Chiroubles are situated somewhat higher than those of the other crus.

🎧 Need a refresher course? Then listen to the podcast about the Bojo >

The high vineyards of Chiroubles

Chiroubles is known for its relatively high vineyards. Roughly between 250 and 500 meters. That's quite a feat by Beaujolais standards. The primary effect of these higher vineyards is a cooling effect. Generally, Chiroubles is the last vineyard to be picked of all the crus. And that's noticeable in the average Chiroubles. They're usually the freshest of the bunch. Or mineral, if you're not afraid of that word. Incidentally, the altitude and its associated cooling effects have come in handy in recent years: since 2015, there hasn't been a single year in Beaujolais that wasn't very hot. Something you can clearly taste in the wines.

Beaujolais from recent years can sometimes be quite sunny, jammy, and alcoholic. Wines with 14.5% alcohol are no exception. Something that, in my opinion, sometimes contrasts slightly with the lighthearted, juicy, and cheerful character that should characterize a Beaujolais. The wines from Chiroubles remain somewhat lighter even in warm vintages. And if you enjoy classic Beaujolais, such as it was made in 2014, for example, this is a godsend. Because of their lighthearted character, wines from Chiroubles are also excellent for drinking young, unlike the sometimes more robust wines from Morgon or Moulin-á-Vent. Those can, or should, take a while to truly enjoy. Unfortunately, there isn't a star producer in Chiroubles. No Lapierre, Thivin, or Dutraive, for example.

Many farmers from Morgon and Fleurie (the two neighboring crus) often have one or more vineyards in Chiroubles, but often consider it a bonus. Fortunately, there are a few noteworthy Chiroubles. Like that of Jules Metras, indeed, the son of (Yvon Metras, Fleurie). He makes a very good one, entirely in his father's style, deliciously juicy and natural. Or how about the Chiroubles 'Chatenay' from Daniel Bouland, you know, that idiosyncratic producer of old-school, muscle-bound Beaujolais?

Wine tip: Jules Metras / Chiroubles / Wine friend

Daniel Bouland's muscle-bound boojos

Beaujolais generally has the image of wines that are released very young and should be consumed as soon as possible. This is certainly true for Beaujolais Primeur. But some wines can last quite a while. From a better cru from a better producer, they can easily last two or three years. And some producers are even known for their wines with ageing potential.

The same goes for the wines of Daniel Bouland from Morgon. I'd even venture to say they're subject to a storage requirement. Bouland, a winemaker who doesn't care about anyone and makes wine entirely in his own unique way, is best known for his uncompromising Morgons, with his flagship being 'Morgon Les Delys Vieilles Vignes de 1926'. Indeed, from vines dating back to 1926.

If you particularly appreciate light, youthful, and fruity Beaujolais, then Bouland will be a real treat. He makes structured wines from ripe grapes, classically trained, and quite lively in their youth. You just have to love them. It's definitely worth a try. Although I recommend everyone wait at least three years before drinking his wines. I've tasted Bouland wines with alcohol levels exceeding 14.5%, and where the nose, as well as the structure, almost reminded me of wines from the Northern Rhône. Which isn't surprising, since that region begins just a few dozen kilometers south of Beaujolais.

Daniel Bouland / Morgon 'Les Delys' / De Bruijn Wine Merchants

Between Burgundy and Northern Rhône

More often than not, you hear at blind tastings, "It looks like Northern Rhône!" or "Just like Burgundy!" While it's a Beaujolais. Many Beaujolais wines sometimes have the characteristic of smelling and tasting slightly different from the stereotypical fruity, sometimes candy-like style. This depends on the terroir, the ripeness of the grapes, and the vinification process (see my previous piece on Beaujolais ), but also the age of the wine.

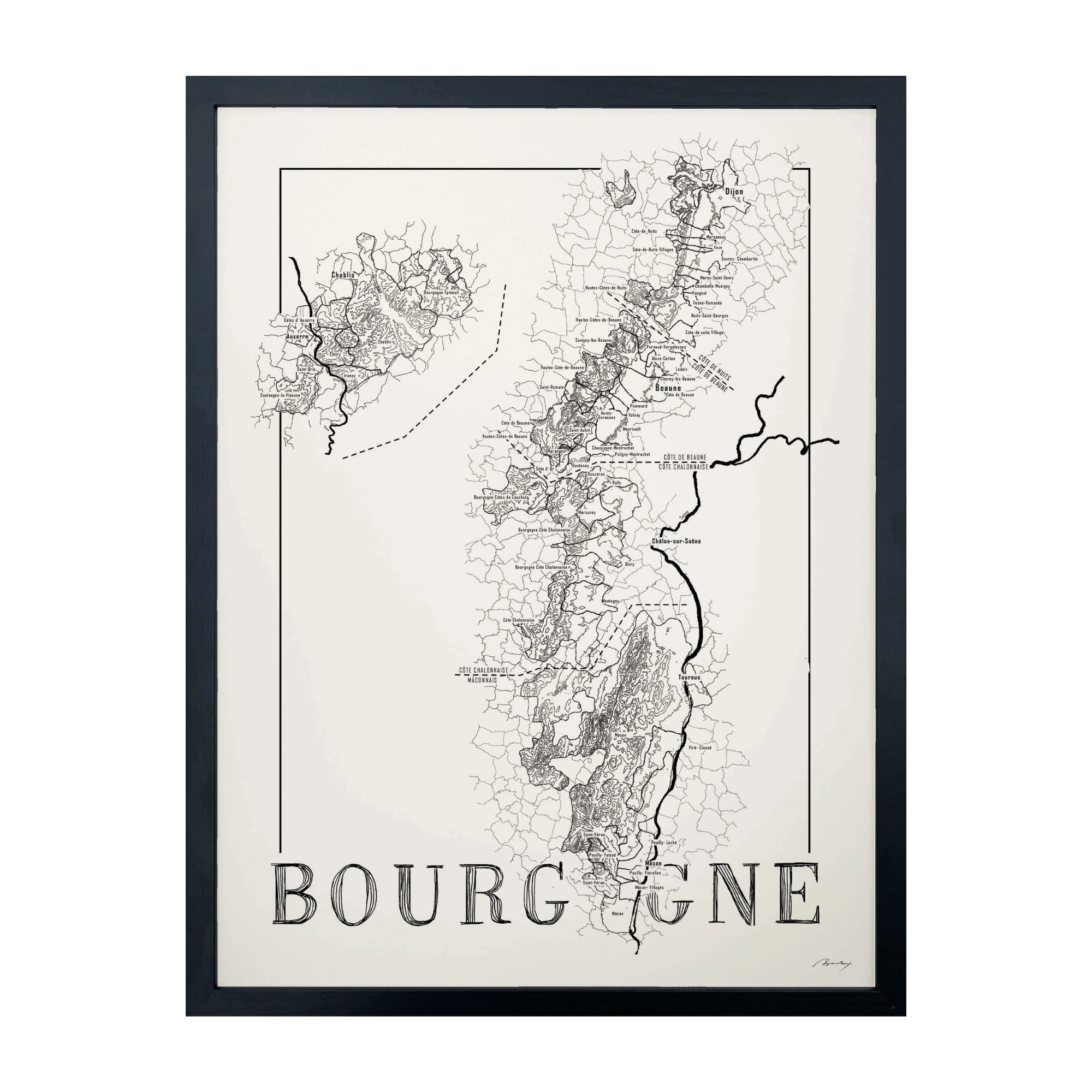

A well-aged Morgon can indeed sometimes taste like a Pinot Noir from Burgundy. Or a Morgon from Daniel Bouland can be reminiscent of a Syrah from the Northern Rhône. This isn't entirely coincidental, as Beaujolais also lies geographically right between those two regions. In some cases, it also has to do with the winemaker's perspective and experience.

One of the most surprising producers from the "just Burgundy" camp I discovered last year was Anne-Sophie Dubois from Fleurie. A young winemaker, with roots in Champagne and experience from Volnay, she's independently crafting a series of beautiful Fleuries. In a light, fragrant, and—indeed—Burgundian style, thanks in part to the aging of the wines.

Anne-Sophie Dubois / Fleurie l'Alchemiste / Emerald Wines

Chenas and the wines of Paul-Henri Thillardon

Ultimately, it's always the producer who determines what type of wine lies behind the label. And therefore, whether their Fleurie should taste like a Fleurie, a completely generic Beaujolais, or, certainly not unthinkable: a natural wine plagued by wine faults. Natural wine is produced in large quantities in the Beaujolais, not least because the godfather of natural wine, Marcel Lapierre, once started in Morgon.

Today, dozens, if not hundreds, of farmers operate according to Lapierre's principles: "nothing in, nothing out." Wine is made from organically or biodynamically grown grapes, with minimal alterations in the cellar. Natural wine, in other words. A risky undertaking, although I generally find the quality of natural wine in Beaujolais to be high.

Of the new generation, Paul-Henri Thillardon is perhaps one of the very best. Perhaps because he's trying to put Chénas, that notoriously overlooked cru, on the map. Chénas is the smallest cru of the ten, located near Moulin-á-Vent, capable of producing somewhat more robust wines, and, unfortunately, relatively unpopular in Belgium. Fortunately, there are the not-too-inexpensive wines from Thillardon, who makes separate bottlings from various vineyards in Chénas. Quite ambitious, considering Chénas has little to no real reputation, let alone the individual vineyards, such as Les Blémonts and Chassignol. Why not one or two excellent blends, such as Lapierre's Morgon or Yvon Metras, with his iconic Fleurie?

On the other hand: his various Chénas wines—he now makes four—are all highly recommended, with Chassignol, from a vineyard entirely owned by him, being the standout. Thillardon practices biodynamics in his vineyards and takes considerable risk in his cellar: fermenting whole bunches at an absurdly low temperature of around 9 degrees Celsius. This results in a very long fermentation, but it results in beautifully complex, subtle, and exceptionally fruity and peppery wines.

Paul-Henri Thillardon / Chénas 'Les Blémonts' / Bosman Wine Merchants

Outside the crus

We're all familiar with those ten crus by now. Fortunately, there's also the Beaujolais-Villages AOC. This AOC designates the 38 villages and communes in and around the crus, and I doubt anyone can recite them all, preferably in staccato. Beaujolais-Villages is a rather unfortunate AOC anyway, as many consumers barely distinguish between Beaujolais and Beaujolais-Villages.

Well, in short: the AOC Beaujolais actually covers the entire Beaujolais region, including the primeur wines. AOC Beaujolais-Villages, where primeur wines are also produced, comes from the northern, granitic region. This is essentially the area of the 10 Crus, but much larger, as many surrounding villages share the same soil type. A total of 38 villages are located there.

These granite soils are considered perfect for the rather fast-growing Gamay grape, as they are relatively poor, restricting vine growth and improving grape quality. Naturally, there are subtle differences in soil, altitude, and vineyard location. Nevertheless, some of the villages now part of Beaujolais Villages are being touted as promising candidates: villages that may one day become 11th, 12th, and/or 13th Crus.

The most frequently mentioned: Lantignié. A high concentration of pink granite has been found in the soil here, just like the neighboring Regnié, which is a cru. In fact, many Beaujolais insiders consider the terroir of Lantignié superior to that of Regnié, which will be discussed later.

Many Lantignié grapes end up in wines labeled only as Beaujolais-Villages (or, in some cases, just Beaujolais). This is often because these are blended wines, as blending wines from different villages is permitted. For connoisseurs, it's not clear how clear it is: a wine made from Lantignié grapes can be bottled as Beaujolais, Beaujolais-Villages, or Beaujolais-Lantignié. For many, only Beaujolais is of interest. And yet, Lantignié is actually a not-quite-cru.

Jean-Marc Burgaud, best known for his wines from Morgon, does make a Beaujolais-Lantignié, the short version of which is: it tastes like a cru, but with the price tag of a Beaujolais-Villages. Another excellent wine from Lantignié is that of rising star David Chapel. But he bottles it as Beaujolais-Villages, even though the grapes are 100% Lantignié-grown. And speaking of Beaujolais-Villages: perhaps one of the very best is made by cult winemaker Jean-Claude Lapalu.

Between two generations

Jean-Claude Lapalu began bottling his own wines in 1995. This makes him part of the second generation of natural winemakers, some 15 years after the first. A lost generation? Absolutely not! And certainly not in the case of Lapalu. Lapalu's wines are excellent and highly regarded worldwide. Interestingly, in addition to several Beaujolais-Villages, he also produces Brouilly, a cru that, while the largest in size and production, is somewhere near the bottom in terms of reputation and average quality. However, this doesn't apply to Lapalu's Brouilly. It's excellent. And he's not afraid to experiment. For example, he makes a Brouilly fermented in amphorae: his Brouilly 'Alma Mater'. An exceptionally robust, distinctive wine. Or how about his Beaujolais-Villages 'Le Rang du Merle', which is strikingly bottled in a Bordeaux bottle, which is especially unusual in Beaujolais. Lapalu's wines are distinctly natural, sometimes a bit funky, but never bad. Even his entry-level wines are still very energetic after about five years.

Jean-Claude Lapalu / Beaujolais-Villages VV / Herman Wines

Rising prices

For many, Beaujolais still has the image of a low-priced, underrated wine. And believe me, in a French supermarket, you won't have to go far to find undrinkable Beaujolais for, say, €3.50. Paying ten times that price for a stylish Morgon or Fleurie from a natural producer, preferably with a strikingly designed label, is no problem either.

Land is generally still very cheap in Beaujolais, making it an affordable place for emerging winemakers to establish themselves. Moreover, the region and the Gamay grape lend themselves to making natural wine, and many new farmers are trained this way, so it's understandable that many contemporary producers operate this way. This is a labor-intensive and risky approach. Many new wines then easily cost at least 25 euros, which, incidentally, they're not always worth. It's all the more rewarding to sometimes find estates that produce very good wines at traditional prices.

Domaine Montangeron is one of them. Fleurie, Morgon, and Chiroubles wines with unappealing labels, but with plenty of compensating content. Especially from the warm vintages of '18 and '19, bursting with fruit and pleasure. And available in the Netherlands for under ten euros.

Domaine Montangeron / Fleurie / Henri Bloem

The last cru

The for Dutch people Régnié, so difficult to pronounce, still needs to be mentioned. As mentioned earlier, this village was the last to be promoted to cru: in 1988 to be precise. The late George Duboeuf, commercial godfather of Beaujolais, managed to promote the village of Beaujolais-Villages to cru through clever lobbying. Because he owned many vineyards there himself.

A nice bonus is that Régnié, besides being the village of excessive accent graves, is the place where the Romans once planted the first vines in Beaujolais. These days, we don't actually see much Régnié on the shelves. It's a somewhat difficult cru to pinpoint, with a few noteworthy wines, such as the 'Grain & Granit' from Charly Thévenet, son of the "no-sulphur" gang member Jean-Paul Thévenet. And, perhaps my favorite—because he's a truly excellent producer—that of Julien Sunier.

Julien is a former student of Burgundy greats like Nicolas Potel and Christophe Roumier (whose barrels he still uses to age his wines) and has vineyards in Fleurie, Morgon, and Régnié. He even makes a wine from Lantignié, but its label is prominently labeled "Wild Soul" instead of the village name. While many in Beaujolais felt the village of Lantignié deserved far more promotion than Régnié. So you see, life isn't always fair. Fortunately, Sunier's wines are.

Julien Sunier / Regnié / Janselijn

Conclusion: drink more Beaujolais

Beaujolais is a region that long suffered from its bad reputation, mainly due to the Beaujolais Nouveau craze, which, starting in the mid-20th century, forced much Beaujolais to be primarily simple and inexpensive. Crus were overshadowed, and anything labeled Beaujolais was declared equivalent to Beaujolais Nouveau.

Overfertilization, excessive pesticides, high yields, excessive chaptalization, and poor winemaking practices all contributed to the deterioration of the wines. Fortunately, a shift is underway, and more and more enthusiasts, including in the Netherlands, are appreciating good Beaujolais. And the names of the crus, especially those of Morgon, Moulin-á-Vent, and Fleurie, are becoming increasingly well-established.

Unfortunately, due to the coronavirus crisis, much Beaujolais is currently being left behind, partly because these wines are normally served frequently in Parisian and Lyonnais restaurants. Fortunately, every wine merchant in the Netherlands now has good Beaujolais, and with spring on its way, the motto is: drink more Beaujolais!

Share:

Mats wants to become a Master of Wine (part 2)

Médoc in a nutshell