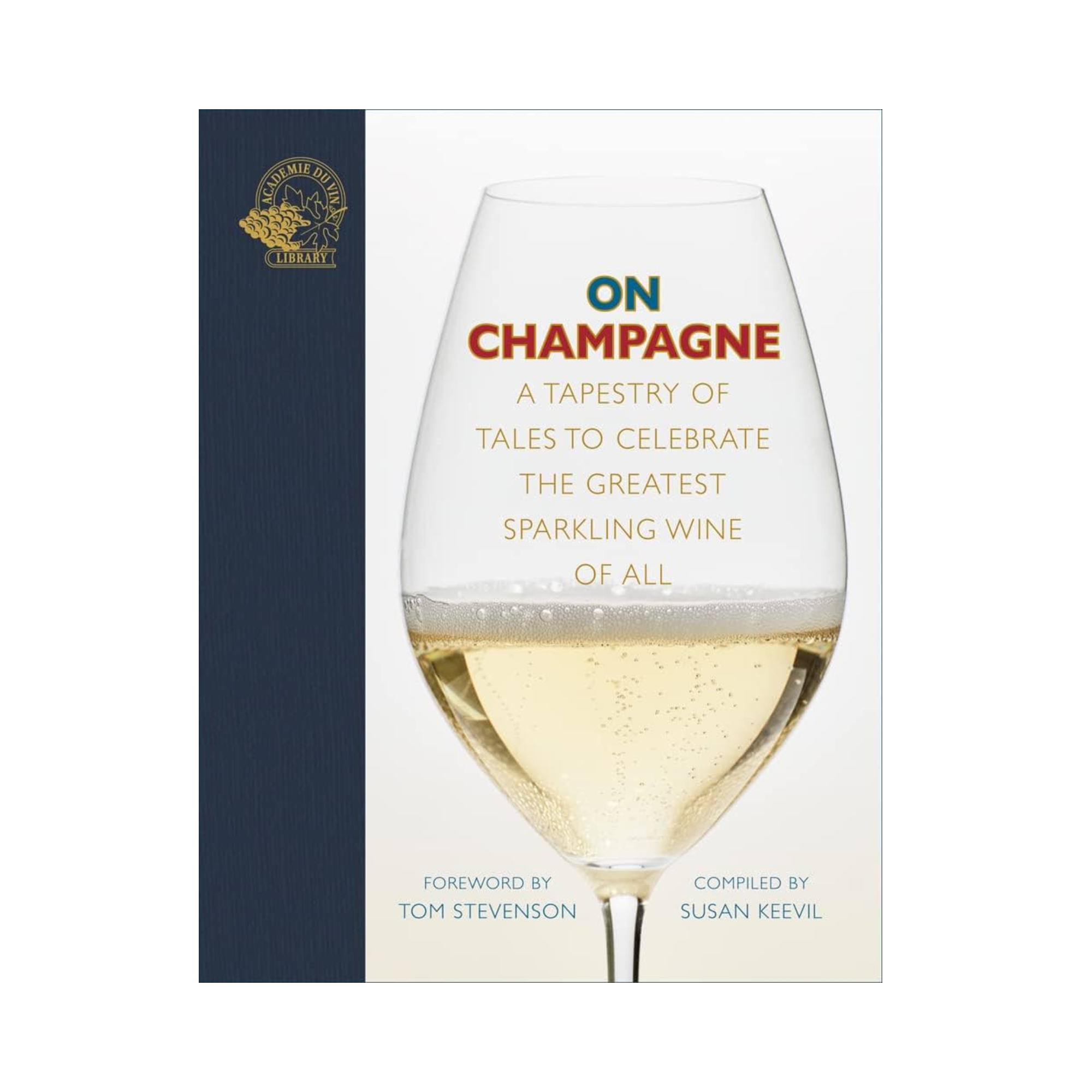

I still can't believe it. Yesterday I tasted a Bollinger Vieilles Vignes Françaises for the first time. Champagne, that is.

Okay—you might be thinking—you were drinking champagne again? True, but this was so much more than that. It was a what-if moment that pierced my very marrow. Time stopped, and my head started spinning… What if I hadn't pursued graduate school? What if I hadn't gone to France during that program? What if I'd never become captivated by wine? What if the devastating grape louse phylloxera hadn't hit Europe?

Devastating phylloxera

That last point hits the nail on the head. Phylloxera, a grape louse, is practically the vineyard's worst enemy. Due to human intervention, the louse arrived in Europe from America in the late 1800s and spread rapidly. Entire wine regions were devastated, and an international wine shortage ensued. There was complete panic. The Minister of Agriculture and Commerce offered a reward of 20,000 francs (equivalent to 1 million euros today) to anyone who could cure the vines.

After trying everything—including spreading seeds dissolved in sulfuric acid over the vineyards—a Chilean finally came up with a solution. American vines proved resistant to the louse. Winegrowers across Europe began grafting their European grape varieties onto American rootstock (source).

Magical vineyards

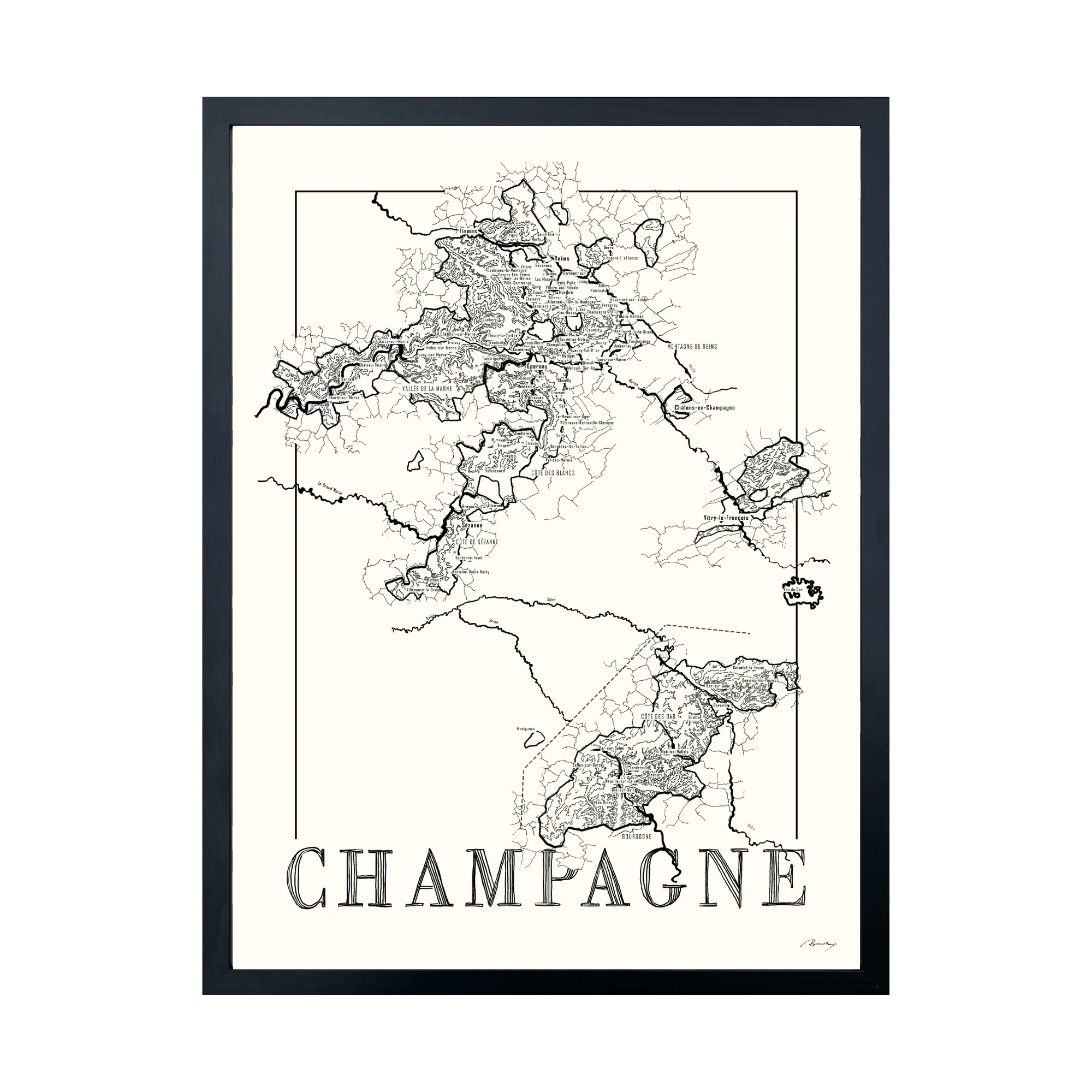

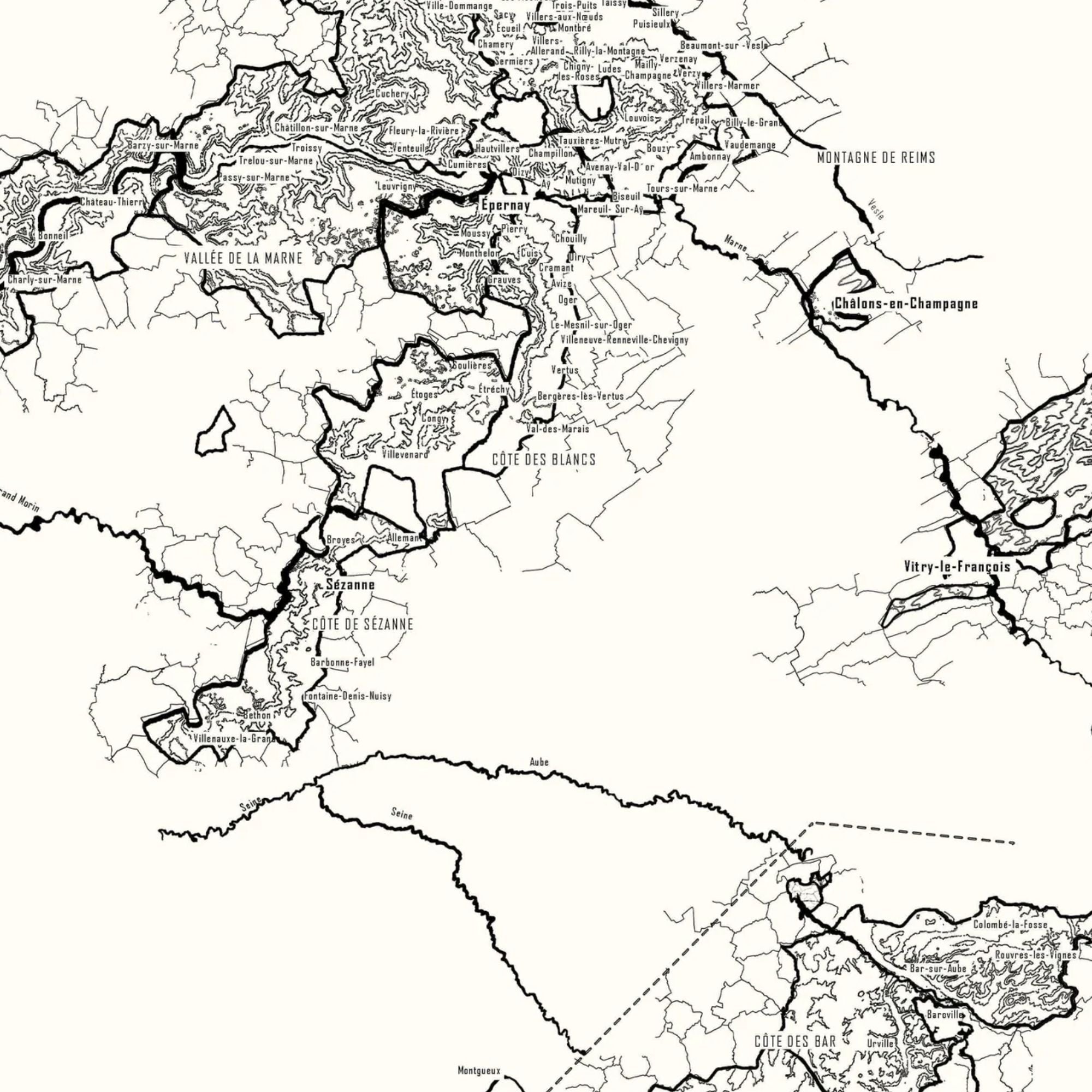

Miraculously, three small plots of Pinot Noir vineyards in Champagne were spared. These plots were (and still are) owned by Champagne house Bollinger. Two of the vineyards are located in Ay, Chaudes Terres and Clos St-Jacques, and the other, Croix Rouge, is located in Bouzy. The vineyards are still extremely vulnerable. Unfortunately, phylloxera struck Croix Rouge in 2004 and is now also out of commission.

The other two together total 0.45 hectares, which is good for about 3,000 bottles per year. That is, if the year is good enough to release a vintage. For this wine, Bollinger uses only the first pressing—meaning 4,000 kg of grapes are pressed very gently. This 4,000 kg results in a maximum of 2,050 liters of must—this is called the first pressing or tête de cuvée. The same grapes can then be pressed again under slightly higher pressure, known as vin de taille, which may yield a maximum of 500 liters. This second pressing is slightly less concentrated, has lower acidity, and is often rich in tannins (the juice then comes into more contact with the skins and seeds), and therefore Bollinger does not use it.

Young or old?

France wouldn't be France if they didn't make things a bit confusing. "Vieilles vignes" sounds like old vines, but the vines in question are actually quite young. The name refers more to the ancient French "en foule" method used in the vineyard. It's a rather complicated story, but I'll try to explain it.

In these vineyards, it wasn't necessary to graft the vines onto American rootstock. So, original French vines are still here. Original: yes, but old: no. By using this "en foule" method, the top of the vine, the part above the ground, is very young. Every year, it's bent over and put back into the ground. Three buds should be sticking out above the ground so that new branches bearing grapes can grow from them. At the same time, new roots also grow from the branch that goes into the ground. And so it continues every year, with the vine gradually shifting (source).

Wow, that's a complicated story. I hope I can make a trip to Bollinger next year so I can see it for myself and take pictures ;-).

UPDATE ! I've been there. On February 3, 2018, I looked out and walked through the small vineyard in Ay, the Clos Saint Jacques. And that happened.

Good story: Vieilles Vignes Françaises

The first Vieilles Vignes Françaises to be released was in 1970. Before that, wine from these vineyards was simply included in Bollinger blends. It was Cyril Ray, a British wine writer and Bollinger fan, who suggested creating a separate Champagne from these vineyards.

That was quite unusual in Champagne. Unlike Burgundy, they weren't so focused on terroir or single vineyards, but rather on blending grapes, vintages, and vineyards to achieve a consistent style and quality. That's different today; just think of the grower champagnes of Chartogne-Taillet, Agrapart, and Ulysse-Collin.

How does it taste?

Intense. Eyes closed. Tremendous length. It reminded me of pear/apple/cinnamon cake. Vanilla, dried mango. I've written down a few phrases like that, but then I thought, bye – I'm going to enjoy myself!

To conclude, a nice quote from a New York Times article:

With the lore and romance of history and fantasy, of what might have been, bubbling up from the bottom of each glass, how can Vieilles Vignes Françaises ever be judged as merely a wine?

It's not a wine. It's the dream of a wine.

A Champagne True To Its Roots – New York Times – June 14th, 2006

This tasting was part of a Bollinger masterclass organised by Wijnhandel Peeters and Verlinden Drink & Discover.

Share:

Which wine with vitello tonnato